原发性进行性失语症变体的灰质结构变化

- 作者: Akhmadullina D.R.1, Konovalov R.N.1, Shpilyukova Y.A.1, Fedotova E.Y.1

-

隶属关系:

- Research Center of Neurology

- 期: 卷 4, 编号 4 (2023)

- 页面: 467-480

- 栏目: 原创性科研成果

- URL: https://bakhtiniada.ru/DD/article/view/262949

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.17816/DD567783

- ID: 262949

如何引用文章

详细

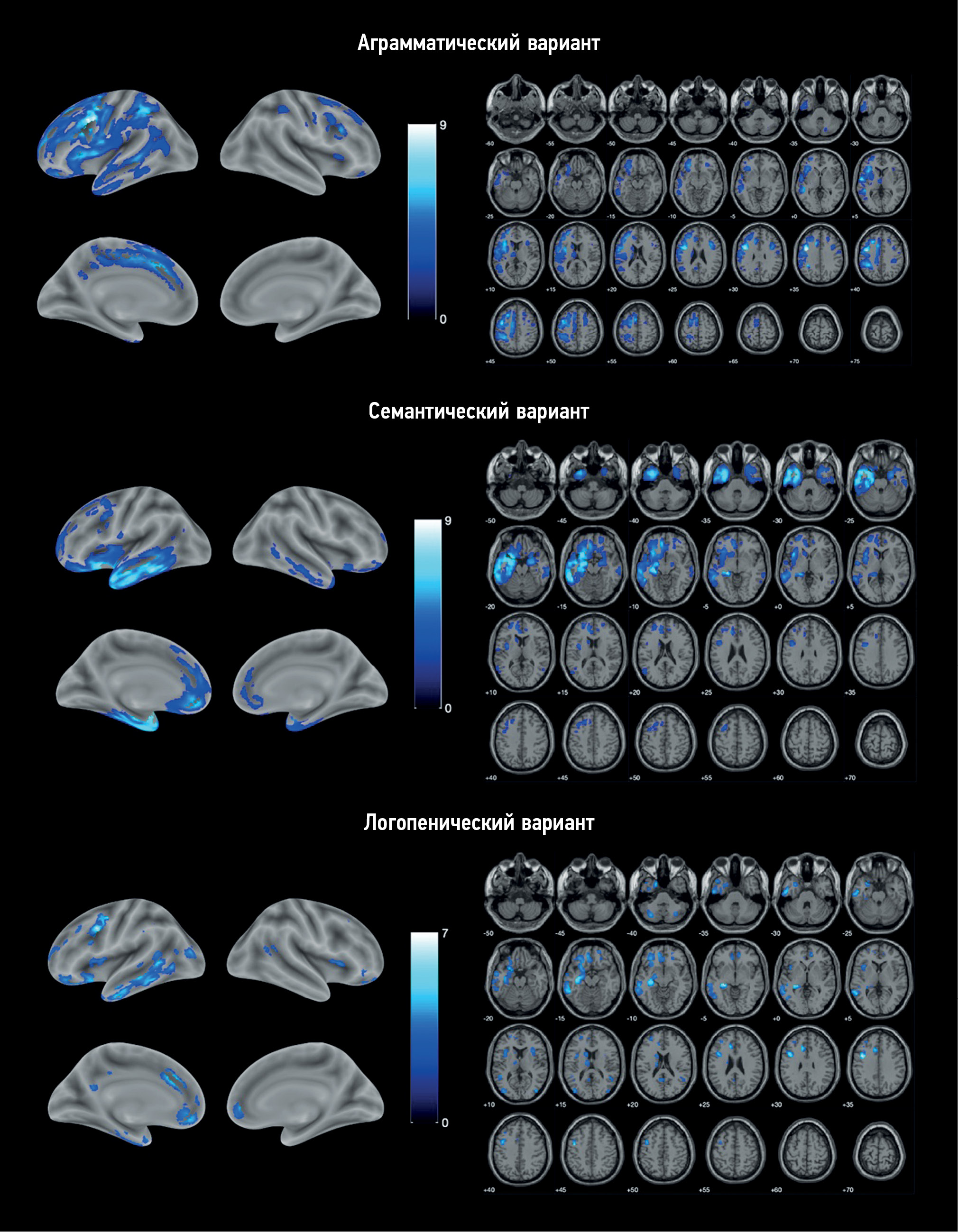

论证。原发性进行性失语症是一种罕见的神经退行性疾病。它的异质性使诊断变得非常复杂。基于体素的形态测量法可对大脑灰质病变进行客观评估,并确定每种疾病变异的萎缩模式特征。这可以改善诊断,也可被用于发病机制的研究。

该研究的目的是确定原发性进行性失语症各变体与对照组相比的萎缩模式。

材料与方法。被诊断为原发性进行性失语症变体之一的患者被纳入主研究组。诊断是根据现行诊断标准确定的。对照组由无神经系统表现和脑结构变化的健康志愿者组成。我们对所有参与者都进行了脑部磁共振成像,随后进行了图像后处理和基于体素的形态测量。对每种疾病变体与对照组的灰质体积进行了比较。研究人员考虑到参与者的性别、年龄和颅内容积。

结果。研究对象包括25名非流利型原发性进行性失语的患者、11名语义型原发性进行性失语的患者和9名logopenic型原发性进行性失语的患者,以及20名健康志愿者。基于体素的形态测量显示了,每种变体都有不同的萎缩模式。在非流利型原发性进行性失语症中,额叶和岛叶主要受累。在语义型原发性进行性失语症中,颞叶和海马主要受累。logopenic型原发性进行性失语症的的特点是额颞叶模式更加弥漫。

结论。在研究过程中,我们发现了原发性进行性失语症各变体特有的脑萎缩模式。基本上,这些结果与疾病的临床表现相符。但是有些研究结果(logopenic型没有后外侧裂部位萎缩和有运动皮层病变;非流利型有眶额皮质和小脑病变;语义型有运动前皮层、中央前回和额下回病变)与原发性进行性失语症发病机制的通常观点不符,需要进一步研究。

关键词

作者简介

Diliara R. Akhmadullina

Research Center of Neurology

编辑信件的主要联系方式.

Email: akhmadullinadr1@gmail.com

ORCID iD: 0000-0001-6491-2891

SPIN 代码: 5721-8567

俄罗斯联邦, Moscow

Rodion N. Konovalov

Research Center of Neurology

Email: krn_74@mail.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0001-5539-245X

SPIN 代码: 2515-7673

Scopus 作者 ID: 23497502900

Researcher ID: B-6834-2012

MD, Cand. Sci. (Med.)

俄罗斯联邦, MoscowYulia A. Shpilyukova

Research Center of Neurology

Email: jshpilyukova@gmail.com

ORCID iD: 0000-0001-7214-583X

SPIN 代码: 7502-8984

MD, Cand. Sci. (Med.)

俄罗斯联邦, MoscowEkaterina Y. Fedotova

Research Center of Neurology

Email: ekfedotova@gmail.com

ORCID iD: 0000-0001-8070-7644

SPIN 代码: 3466-2212

MD, Dr. Sci. (Med.)

俄罗斯联邦, Moscow参考

- Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011; 76(11):1006–1014. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821103e6

- Bisenius S, Neumann J, Schroeter ML. Validating new diagnostic imaging criteria for primary progressive aphasia via anatomical likelihood estimation meta-analyses. European Journal of Neurology. 2016;23(4):704–712. doi: 10.1111/ene.12902

- Lombardi J, Mayer B, Semler E, et al. Quantifying progression in primary progressive aphasia with structural neuroimaging. Alzheimer’s & Dementia. 2021;17(10):1595–1609. doi: 10.1002/alz.12323

- Chapman CA, Polyakova M, Mueller K, et al. Structural correlates of language processing in primary progressive aphasia. Brain Communications. 2023;5(2). doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcad076

- Canu E, Agosta F, Battistella G, et al. Speech production differences in English and Italian speakers with nonfluent variant PPA. Neurology. 2020;94(10):e1062–e1072. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008879

- Akhmadullina D, Konovalov R, Shpilyukova Y, et al. Brain atrophy patterns in patients with frontotemporal dementia: voxel-based morphometry. Bulletin of Russian State Medical University. 2020;(6):84–89. doi: 10.24075/brsmu.2020.075

- Lampe L, Huppertz HJ, Anderl-Straub S, et al. Multiclass prediction of different dementia syndromes based on multi-centric volumetric MRI imaging. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2023;37:103320. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2023.103320

- Staffaroni AM, Ljubenkov PA, Kornak J, et al. Longitudinal multimodal imaging and clinical endpoints for frontotemporal dementia clinical trials. Brain. 2019;142(2):443–459. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy319

- zenodo.org [Internet]. spunt/bspmview: BSPMVIEW v.20161108 (Version 20161108). Zenodo. [cited 26 July 2023]. Available from: https://zenodo.org/badge/latestdoi/21612/spunt/bspmview doi: 10.5281/zenodo.168074

- Gorno-Tempini ML, Dronkers NF, Rankin KP, et al. Cognition and anatomy in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Annals of Neurology. 2004;55(3):335–346. doi: 10.1002/ana.10825

- Tetzloff KA, Utianski RL, Duffy JR, et al. Quantitative analysis of agrammatism in agrammatic primary progressive aphasia and dominant apraxia of speech. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2018;61(9):2337–2346. doi: 10.1044/2018_JSLHR-L-17-0474

- Whitwell JL, Duffy JR, Strand EA, et al. Distinct regional anatomic and functional correlates of neurodegenerative apraxia of speech and aphasia: An MRI and FDG-PET study. Brain and Language. 2013;125(3):245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2013.02.005

- Mandelli ML, Vitali P, Santos M, et al. Two insular regions are differentially involved in behavioral variant FTD and nonfluent/agrammatic variant PPA. Cortex. 2016;74:149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2015.10.012

- Cordella C, Quimby M, Touroutoglou A, et al. Quantification of motor speech impairment and its anatomic basis in primary progressive aphasia. Neurology. 2019;92(17):e1992–e2004. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007367

- Breining BL, Faria AV, Tippett DC, et al. Association of Regional Atrophy With Naming Decline in Primary Progressive Aphasia. Neurology. 2023;100(6):e582–e594. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000201491

- Rogalski E, Cobia D, Harrison TM, et al. Progression of language decline and cortical atrophy in subtypes of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology. 2011;76(21):1804–1810. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821ccd3c

- Samra K, MacDougall AM, Bouzigues A, et al. Genetic forms of primary progressive aphasia within the GENetic Frontotemporal dementia Initiative (GENFI) cohort: comparison with sporadic primary progressive aphasia. Brain Communications. 2023;5(2). doi: 10.1093/braincomms/fcad036

- Rohrer JD, Nicholas JM, Cash DM, et al. Presymptomatic cognitive and neuroanatomical changes in genetic frontotemporal dementia in the Genetic Frontotemporal dementia Initiative (GENFI) study: a cross-sectional analysis. The Lancet Neurology. 2015;14(3):253–262. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70324-2

- McKenna MC, Li Hi Shing S, Murad A, et al. Focal thalamus pathology in frontotemporal dementia: Phenotype-associated thalamic profiles. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2022;436:120221. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2022.120221

- Ziegler W, Ackermann H. Subcortical Contributions to Motor Speech: Phylogenetic, Developmental, Clinical. Trends in Neurosciences. 2017;40(8):458–468. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2017.06.005

- Migliaccio R, Boutet C, Valabregue R, et al. The Brain Network of Naming: A Lesson from Primary Progressive Aphasia. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(2):e0148707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148707

- Wisse LEM, Ungrady MB, Ittyerah R, et al. Cross-sectional and longitudinal medial temporal lobe subregional atrophy patterns in semantic variant primary progressive aphasia. Neurobiology of Aging. 2021;98:231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2020.11.012

- Fittipaldi S, Ibanez A, Baez S, et al. More than words: Social cognition across variants of primary progressive aphasia. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2019;100:263–284. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2019.02.020

- Brown JA, Deng J, Neuhaus J, et al. Patient-Tailored, Connectivity-Based Forecasts of Spreading Brain Atrophy. Neuron. 2019;104(5):856–868.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.08.037

- Collins JA, Montal V, Hochberg D, et al. Focal temporal pole atrophy and network degeneration in semantic variant primary progressive aphasia. Brain. 2017;140(2):457–471. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww313

- Kumfor F, Landin-Romero R, Devenney E, et al. On the right side? A longitudinal study of left- versus right-lateralized semantic dementia. Brain. 2016;139(3):986–998. doi: 10.1093/brain/awv387

- Henry ML, Wilson SM, Babiak MC, et al. Phonological Processing in Primary Progressive Aphasia. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2016;28(2):210–222. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00901

- Montembeault M, Brambati SM, Gorno-Tempini ML, Migliaccio R. Clinical, Anatomical, and Pathological Features in the Three Variants of Primary Progressive Aphasia: A Review. Frontiers in Neurology. 2018;9. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00692

- Bergeron D, Gorno-Tempini ML, Rabinovici GD, et al. Prevalence of amyloid-β pathology in distinct variants of primary progressive aphasia. Annals of Neurology. 2018;84(5):729–740. doi: 10.1002/ana.25333

- Preiß D, Billette OV, Schneider A, et al. The atrophy pattern in Alzheimer-related PPA is more widespread than that of the frontotemporal lobar degeneration associated variants. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2019;24:101994. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101994