Применение метадискурсивных маркеров в аргументативных эссе, написанных на родном (L1) и английском (L2) языках турецкими студентами, изучающими английский язык как иностранный

- Авторы: Гючлю Р.1, Онем Э.Э.2

-

Учреждения:

- Газиантепский университет

- Университет Эрджиес

- Выпуск: Том 29, № 3 (2025)

- Страницы: 573-594

- Раздел: Академическое письмо

- Статья получена: 25.06.2025

- Статья одобрена: 28.08.2025

- Статья опубликована: 22.09.2025

- URL: https://bakhtiniada.ru/1991-9468/article/view/297585

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.15507/1991-9468.029.202503.573-594

- EDN: https://elibrary.ru/pmandu

- ID: 297585

Цитировать

Полный текст

Аннотация

Введение. Использование метадискурса способствует взаимодействию между автором и читателем, а также когерентности текста. Несмотря на большой интерес ученых к теме включения этих риторических средств в аргументативные эссе обучающихся, сравнительные исследования маркеров метадискурса в работах студентов, для которых турецкий язык является родным (L1), а английский – вторым (L2), не получили должного внимания. Цель исследования – выяснить, используют ли турецкие студенты – носители языка элементы метадискурса в своих аргументативных эссе на турецком (L1) и английском (L2) языках, написанных на уровне ниже среднего.

Материалы и методы. На основе межличностной модели метадискурса был проведен сравнительный анализ корпуса из 200 эссе (100 эссе на турецком языке, 100 – на английском). Элементы метадискурса определены с помощью корпусного подхода. После выявления использования маркеров метадискурса было проведено количественное исследование с применением тестов SPSS с целью установления различий между эссе на турецком и английском языках. Способы применения студентами маркеров метадискурса для достижения аргументативных целей определялись путем качественного анализа.

Результаты исследования. Внутриязыковой и межъязыковой анализ выявил наличие всех категорий метадискурса в корпусах, каждая из которых выполняет определенные функции. Часто используемой категорией как в турецких, так и в английских эссе оказались самоупоминания. Метадискурсивные маркеры используются изучающими английский как иностранный в качестве риторических средств с целью создания аргументированных, удобных для чтения и связных текстов, что позволяет лучше понять выразительные способности студентов в аргументированном дискурсе.

Обсуждение и заключение. Подчеркивая эффективность метадискурсивных маркеров как риторических инструментов, результаты исследования показывают, что явное обучение этим маркерам может значительно повысить уровень владения письменной речью и успешность аргументации у студентов. Преподаватели могут включать в учебный процесс задания, направленные на выявление, анализ и стратегическое использование различных категорий метадискурса, чтобы помочь учащимся создавать более сложные письменные коммуникации. Материалы статьи имеют важное значение для преподавания языка, особенно в контексте EFL.

Полный текст

Introduction

Effective academic writing involves more than the accurate transmission of propositional content. It also requires a purposeful organization of ideas that guides the reader through the argument and facilitates comprehension1 [1]. This rhetorical structuring is often achieved through metadiscourse, a set of linguistic resources that signal the writer’s stance, organize information, and create a connection with the reader. In English as a Foreign Language (EFL) contexts, the ability to use metadiscourse markers (MDMs) effectively is a crucial element of academic literacy, contributing to textual coherence, rhetorical persuasiveness, and reader engagement. Although metadiscourse has been recognized as an important component of written communication, it remains comparatively underrepresented in EFL instruction and in empirical research that addresses its use in both L1 and L2 writing.

Metadiscourse can be defined as language that reflects upon and comments on discourse itself2. It functions at a meta-level, shaping how readers interpret, evaluate, and organize information. Early frameworks such as W.J. Vande Kopple’s3 model distinguished between textual resources, which promote cohesion and coherence, and interpersonal resources, which convey the writer’s attitude and commitment to the reader. A. Crismore et al. refined this taxonomy by dividing the textual category into textual and interpretive markers, thereby emphasizing the role of the reader in meaning-making4. K. Hyland and P. Tse [2] advanced the field by differentiating between interactive resources, which organize discourse for readers, and interactional resources, which project the writer’s stance and invite reader engagement. K. Hyland’s5 Interpersonal Model has since become one of the most widely used frameworks due to its functional clarity, pedagogical relevance, and applicability to both professional and student writing.

Research on metadiscourse in L2 student writing has grown considerably in the past two decades6 [3]. Studies consistently highlight the role of MDMs in developing rhetorical competence, guiding the reader’s interpretation, and enhancing argumentative effectiveness. Evidence shows that metadiscourse use is shaped not only by linguistic proficiency but also by L1 rhetorical traditions, genre conventions, and the nature of instructional practices [4–6]. Many comparative investigations have reported an underuse of interactional elements, particularly hedges and engagement markers, across a variety of cultural contexts, suggesting gaps in rhetorical training [7; 8]. Other findings challenge these patterns. For example, N. Al-Wazeer and A. Ashuja’a [9] observed no significant cultural differences between L1 and L2 writers of legal texts, which suggests that disciplinary norms can outweigh cultural influences. Pedagogical innovations such as flipped learning [10] and AI-assisted writing support [11] have been shown to increase metadiscourse awareness and to encourage a shift from predominantly structural to more rhetorically strategic usage.

Comparative studies of L1 and L2 writing reveal that MDM use reflects the combined influence of academic culture, genre requirements [12–14], and teaching context7 [15–16]. The findings are not always consistent. C.G. Zhao and J. Wu [16] report that learners may exhibit a stronger authorial voice in L2 writing, whereas R. Jančaříková [17] found an overuse of attitude markers in L2 texts, which can indicate discursive imbalance rather than rhetorical confidence. Cross-linguistic transfer of L1 rhetorical habits into L2 writing is frequently observed [18], although in some genres common discourse patterns emerge across linguistic backgrounds [19]. Such contradictions underline the importance of context-specific, genre-controlled research.

Within the Turkish EFL context, existing research is relatively limited in scope compared with studies on other learner groups such as East Asian or Middle Eastern students. Previous investigations have examined hedging and boosting in argumentative texts8, the distribution of a wider range of MDM categories9 [20], and discourse features across genres [21; 22]. Results have pointed to both similarities and differences between L1 and L2 writing, sometimes departing from patterns reported in Anglophone contexts10. More recent studies have focused on developmental and disciplinary variation in MDM use [23; 24] and on broader rhetorical trends [25]. However, these studies predominantly involve advanced learners, frequently lack control over genre and topic, and rarely address the writing of lower-proficiency students.

Another important but underexplored dimension concerns the relationship between metadiscourse use and academic culture, understood as a set of norms governing knowledge presentation and authorial positioning in specific scholarly communities [26]. E. Tikhonova’s work shows that rhetorical organization and interactional choices are shaped not only by language competence but also by culturally embedded discourse models. This suggests that L1–L2 comparisons should be seen not merely as a linguistic exercise but as a socio-rhetorical inquiry that explores how writers adapt stance and engagement strategies across languages.

Despite the growing body of literature, there is still a lack of studies examining how the same learners employ metadiscourse markers (MDMs) in parallel L1 and L2 writing tasks under equivalent conditions. This gap is particularly evident at the pre-intermediate level and in the Turkish context, where comparative research with strict control of topic, genre, and writer cohort is scarce. The purpose of this study is to investigate the use of interactive and interactional metadiscourse in argumentative essays written in Turkish (L1) and English (L2) by the same group of pre-intermediate EFL learners, in order to address this research gap. The research addresses two questions:

- Do learners use metadiscourse markers differently in L1 and L2 argumentative essays?

- How do interactive and interactional markers vary in function and frequency across the two languages?

By controlling for genre, topic, and writer identity, this study provides a detailed account of cross-linguistic influences, transfer effects, and the role of instructional context in shaping rhetorical choices. In doing so, it contributes to the broader debate on the relative influence of genre conventions and language background on metadiscourse use. The findings have direct pedagogical implications for genre-based EFL writing instruction that aims to build balanced rhetorical repertoires, increase audience awareness, and prepare Turkish learners to produce coherent, persuasive, and reader-oriented academic texts.

Literature Review

Conceptualizing Metadiscourse. Metadiscourse has been widely defined as language that comments on and organizes discourse itself, operating beyond the propositional content of a text to guide the reader’s comprehension, interpretation, and evaluation11. This notion positions metadiscourse as an integral element of writer – reader interaction, enabling the writer to structure ideas, signal stance, and anticipate audience needs.

W.J. Vande Kopple’s12 early taxonomy divided metadiscourse into textual elements, which enhance cohesion and coherence through devices such as connectives, code-glosses, and illocution markers, and interpersonal elements, which convey the writer’s attitude, commitment, and evaluative stance. A. Crismore et al. refined this model by distinguishing textual markers from interpretive markers, the latter designed to support the reader’s understanding of the writer’s intended meaning13.

Hyland and P. Tse’s [2] reformulation introduced a widely adopted functional distinction between interactive resources, which organize discourse for the reader, and interactional resources, which convey stance and facilitate engagement. K. Hyland’s Interpersonal Model, used in the present study, integrates earlier frameworks while addressing category overlaps and offering a more explicit reader-oriented perspective. Interactive resources include transitions, frame markers, code glosses, endophoric markers, and evidentials, whereas interactional resources include hedges, boosters, attitude markers, self-mentions, and engagement markers. This model has proved particularly effective in research on L1/L2 writing, where it captures differences in both textual organization and interpersonal negotiation.

Metadiscourse in L2 Academic Writing. The past two decades have seen a marked increase in research on metadiscourse in academic writing by L2 learners14 [3]. Findings consistently underscore the role of MDMs in developing rhetorical competence, enhancing cohesion, and fostering persuasive communication. Importantly, studies have demonstrated that metadiscourse use is shaped by a complex interplay of factors that extend beyond linguistic proficiency to include L1 rhetorical norms, genre knowledge, and pedagogical context [4–6].

Several cross-cultural studies have revealed underuse of interactional resources, particularly hedges and engagement markers, in different cultural settings, often interpreted as evidence of limited rhetorical training [7; 8]. However, other research has challenged these generalizations. N. Al-Wazeer and A. Ashuja [9], for example, found no significant differences between L1 and L2 writers of legal texts, suggesting that disciplinary conventions can mitigate cultural variation. Recent pedagogical interventions, such as flipped learning models [10] and AI-assisted writing instruction [11], have been shown to enhance metadiscourse awareness and encourage a shift from purely structural to more strategic rhetorical use.

Despite this growing interest, undergraduate writing has received comparatively less attention than postgraduate, scholarly, or professional genres. This imbalance limits our understanding of how metadiscourse develops in earlier stages of academic writing competence.

Comparative Studies of L1 and L2 Writing. Research comparing L1 and L2 metadiscourse use has highlighted the influence of academic culture, instructional background, and genre conventions15 [12–16]. Learners in different contexts, including EFL, ESL, and EMI settings, often adopt distinct rhetorical strategies, and these patterns are not always consistent. C.G. Zhao and J. Wu [16] reported that L2 writers can display a stronger authorial voice, while R. Jančaříková [17] identified an overuse of attitude markers in L2 texts, suggesting a discursive imbalance rather than enhanced confidence.

Cross-linguistic transfer remains a well-documented phenomenon [18], with L1 rhetorical habits influencing L2 writing. Nevertheless, in some genres, notably academic theses and journalistic writing, shared discourse patterns emerge regardless of L1 background [19]. These mixed findings point to the need for controlled, context-sensitive studies that account for genre, topic, and learner proficiency.

Metadiscourse in the Turkish EFL Context. Compared with East Asian and other Middle Eastern learner groups, Turkish EFL learners have received relatively little systematic attention in metadiscourse research. Earlier studies examined specific features such as hedging and boosting16 or broader MDM repertoires across learner and native speaker groups17 [20]. Results have indicated both cross-linguistic similarities and divergences from patterns typical of Anglophone academic writing18.

Subsequent research has documented developmental trends. D. Beyazyildirim and G.S. Ercan [23] observed that Turkish EFL learners initially used engagement markers and hedges frequently in discussion essays, but this declined over time. Taymaz reported differences between master’s and doctoral theses, with more hedges at the master’s level and more boosters at the doctoral level, possibly linked to evolving academic confidence.

Aykut-Kolay and B. İnan-Karagül [24] found disciplinary variation in verbal metadiscourse in EMI classrooms, suggesting that metadiscourse development is not uniform across contexts. Ö. Oktay et al. [25] compared master’s theses from Turkey and Finland, offering insights into broader rhetorical and methodological norms without focusing directly on metadiscourse. Although not centered on Turkish learners, R. Esfandiari and O. Allaf-Akbary [11] provided relevant evidence on how AI tools such as ChatGPT and Copilot can influence interactional metadiscourse use, highlighting potential pedagogical applications for the Turkish context.

Overall, the existing literature shows a growing awareness of metadiscourse among Turkish EFL learners but remains limited in scope. Most studies focus on advanced learners, employ narrow genre ranges, and often lack control over topic or task conditions.

Present Study. The synthesis of prior research reveals a clear gap in understanding how the same learners use metadiscourse in L1 and L2 writing when genre, topic, and conditions are held constant. This gap is particularly salient at the pre-intermediate level in the Turkish context, where there is little evidence on how MDM use develops and transfers across languages. Furthermore, recent scholarship on academic culture [26] emphasizes that rhetorical choices are shaped not only by linguistic competence but also by culturally embedded norms of scholarly communication. Investigating L1/L2 metadiscourse use from this perspective allows for a richer interpretation of cross-linguistic and cross-cultural influences, as well as the role of instructional context in shaping rhetorical repertoires.

The present study addresses this gap by conducting a controlled comparison of interactive and interactional metadiscourse in L1 Turkish and L2 English argumentative essays written by the same pre-intermediate EFL learners. This approach enables the identification of both convergences and divergences in MDM use, providing insights with direct pedagogical relevance for genre-based writing instruction in EFL settings.

Materials and Methods

Research Design. This study employed a comparative mixed-methods research design to examine how Turkish pre-intermediate EFL learners employ metadiscourse markers in argumentative writing across their L1 (Turkish) and L2 (English). Drawing on K. Hyland’s Interpersonal Model of Metadiscourse, the study combines qualitative discourse analysis (manual annotation) to delve into the specific linguistic manifestations of these markers with descriptive statistical procedures (SPSS analysis) to compare the frequency and distribution of metadiscourse categories in the argumentative essays written by Turkish EFL learners in both their native language (L1 Turkish) and English (L2). This design aligns with the research aim of exploring cross-linguistic rhetorical behaviors within a controlled genre and topic context.

Data Collection Procedure. Participants. The participants comprised 100 Turkish EFL learners (55 female, 45 male; mean age = 20.3) enrolled in a compulsory English course at a public university in Turkey. All participants were pre-intermediate (A2–B1 CEFR) and had not received prior instruction in metadiscourse or academic writing. However, they received instruction in academic writing specifically focusing on composing argumentative essays during the term.

Sample. Argumentative essays offer an ideal genre for exploring metadiscourse because they require students to organize claims, express stance, and engage readers, core functions of metadiscourse. In the present study, argumentative essay format was selected based on Silver’s assertion that academic writing inherently involves persuasion, suggesting that metadiscourse usage would be observable in such writing. Participants were asked to write two argumentative essays on the same prompt: one in Turkish (L1) and the other in English (L2), each consisting of 200–250 words and allowing 40 minutes per essay. The tasks were completed in class without access to external resources, over two consecutive sessions weeks. This design ensured comparability of topic, genre, and rhetorical purpose across both languages. A total of 19,316 words were analyzed considering all the metadiscourse markers, and the high number of participants and essays was considered adequate for statistical analyses.

The selection of 100 L1 and 100 L2 essays was guided by the principle of balanced representation and statistical adequacy. This sample size ensures reliable frequency comparisons while maintaining manageability for qualitative coding, aligning with practices in similar corpus-based EFL studies [3].

Procedure. Participants were instructed to compose argumentative essays in both English and Turkish regarding the factors influencing technology usage. Before the research commenced, ethical approval was obtained from Erciyes University, and informed consent was secured from all participants. Each student voluntarily crafted an argumentative essay in English (L2) at the outset of the term, followed by a Turkish one (L1) at the term’s conclusion, addressing the same topic. The decision to present the L2 essays before the L1 essays in the analysis was informed by prior research suggesting that writing in the native language (L1) could facilitate the process of translation and recollection of ideas initially expressed in the L2 task [27; 28]. This sequencing allows for a potential exploration of how L1 resources might be drawn upon to elaborate or refine the argument presented in the L2 essay.

All essays were written on the same prompt to ensure topic consistency, and participants were from the same instructional group to control for variation in proficiency and instructional exposure. Using the same learners for both languages allowed for a within-subjects design, which helps control for individual variation in proficiency, writing style, and educational background. To minimize topic-related variation, all participants responded to the same argumentative writing prompt in both languages. This approach ensured that differences observed in metadiscourse use could be more confidently attributed to language context rather than differences in topic familiarity or task interpretation.

Data Analysis. Descriptive statistics (means, frequencies, percentages) were calculated using SPSS to identify patterns in the use of metadiscourse categories across L1 and L2 essays. Paired samples t-tests were conducted to determine whether differences in frequency between L1 and L2 texts were statistically significant.

Two researchers independently coded all texts after receiving training based on K. Hyland’s definitions and examples19. All essays were manually annotated for metadiscourse features using K. Hyland’s taxonomy20, which categorizes items into interactive (e.g., transitions, frame markers) and interactional (e.g., hedges, boosters, self-mentions) types. Inter-rater reliability was calculated at 87%, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion with a third expert until consensus was reached. Reliability was measured through Cohen’s kappa (κ = 0.84), indicating substantial agreement. In cases of divergence, a third experienced linguist adjudicated disagreements to finalize the coding scheme.

Analytical Framework. While earlier frameworks, such as W.J. Vande Kopple’s and A. Crismore et al.’s, laid the groundwork for taxonomies of metadiscourse, they differed considerably in how they categorized rhetorical functions21. W.J. Vande Kopple’s distinction between textual and interpersonal metadiscourse focused primarily on surface-level cohesion. In contrast, A. Crismore et al. refined these categories by adding interpretive functions, highlighting the reader’s role in shaping textual meaning. These early models, although significant, paid limited attention to the dynamic interpersonal aspect of writing.

Hyland’s Interpersonal Model marks a significant shift toward emphasizing reader-writer interaction by distinguishing between interactive (organizational) and interactional (evaluative and engagement-oriented) markers22. This distinction gives us a clue about how writers construct stance and guide the reader through the discourse, how writers construct stance and guide the reader through the discourse, making it particularly useful for L1/L2 contrastive studies where rhetorical norms often differ across languages and cultures.

For this study, among the various taxonomies of metadiscourse, K. Hyland’s interpersonal model has gained particular prominence due to its clarity, applicability to student writing, and its balance between textual and reader-oriented features, alongside its concise and thorough categorization23. Accordingly, the analysis of the corpora employed a comprehensive metadiscourse framework encompassing both interactive and interactional categories as outlined in the table below.

T a b l e. K. Hyland’s Interpersonal Model of Metadiscourse

Category | Function | Examples |

Interactive | Help to guide the reader through the text | Resources |

Transitions | Express semantic relation between main clauses | And, in addition, but, consequently |

Frame markers | Refer to discourse acts, sequences, or text stages | Finally, to conclude, my purpose is |

Endophoric markers | Refer to information in other parts of the text | Noted above, see Fig., in Section 2 |

Evidentials | Refer to source of information from other texts | According to X, (Y, 1990), Z states |

Code-glosses | Help readers grasp the meanings of ideational material | Namely, e.g., such as, in other words |

Interactional | Involve the reader in the text | Resources |

Hedges | Withhold the writer’s full commitment to the proposition | Might, perhaps, possible, about |

Boosters | Emphasize force or writer’s certainty in proposition in fact / definitely / it is clear that | In fact, definitely, it is clear that |

Attitude Markers | Express writer’s attitude to pro-position | Unfortunately, I agree, surprisingly |

Engagement Markers | Explicitly refer to or build a relationship with the reader | Consider, note that, you can see that |

Self-Mentions | Explicit reference to author(s) | I, we, my, our |

Source: Compiled by the authors based on data from a book Hyland K. Metadiscourse: Exploring Interaction in Writing. New York: Continuum; 2005. p. 49.

The table show that the interactive category within K. Hyland’s model guides readers through texts, facilitating the flow of information through transitions, frame markers, endophoric markers, evidentials, and code-glosses. These elements were investigated to understand the organization and structure of the argumentative essays. In contrast, the interactional category encompasses hedges, boosters, attitude markers, self-mentions, and engagement markers. These elements serve a multifaceted purpose. They contribute to establishing a distinct authorial voice and demonstrably enhance reader engagement more than interactive metadiscourse markers. The strategic integration of these interactional markers within a text demonstrably improves textual coherence, readability, and the effectiveness of argumentative communication. These features were examined to explore the writer’s stance, interaction with the reader, and the overall modality of the essays.

A corpus-driven methodology was employed for this examination to systematically identify all instances of each category through manual analysis. For example, the phrase “I believe that technology helps people” was annotated as a hedge (I believe) and self-mention (I), while “in other words” was identified as a code gloss. A coding manual was developed with such sample annotations for each MDM subcategory. Furthermore, in annotating the metadiscourse markers, only the most dominant function was counted in cases where multiple functions co-occurred in a single clause. This means that the analysis followed Hyland’s functional approach, grounded in Halliday’s Systemic Functional Linguistics, rather than a micro-level categorization of each linguistic element.

This approach was adopted recognizing metadiscourse as a nuanced concept intertwined with context, thereby precluding precise delineation of its boundaries owing to its multifaceted nature. Additionally, as posited by K. Hyland24, metadiscourse is viewed as an open category, accommodating the incorporation of new elements during text analysis across varied contexts. Therefore, initial coding involved the independent identification and categorization of metadiscourse subcategories within the text by two researchers. Subsequently, the frequency of occurrence for each metadiscourse element was tabulated. To ensure coding reliability and mitigate potential bias, the results from both independent analyses were compared for inter-rater agreement. Any discrepancies in identification or categorization were resolved through consultation with a third expert, ensuring consistency and validity of the data.

Results

This study employs a comparative approach to investigate the utilization of metadiscourse markers in argumentative essays written by Turkish EFL learners. This section presents the findings in accordance with the two research questions:

- Do learners use metadiscourse markers differently in L1 and L2 argumentative essays?

- How do interactive and interactional markers vary in function and frequency across the two languages?

The analysis focuses on essays composed in both their native language (L1 Turkish) and second language (L2 English), drawing upon K. Hyland’s metadiscourse framework25. The analysis revealed both similarities and disparities in the utilization of metadiscourse categories. This section presents the findings of the study, structured into three main parts. The first part examines the overall usage of metadiscourse markers (MDMs) in the argumentative essays written by the participants. The second part delves into the utilization of interactive and interactional MDMs as separate categories. Finally, the third part analyzes the use of specific subcategories within interactive and interactional markers across the two languages (L1 Turkish and L2 English).

General Frequency Comparison (L1 vs. L2 Total Metadiscourse Use). Descriptive statistics and paired samples t-tests revealed that the cumulative number of MDMs was compared inter-linguistically. The data analysis showed that 3,116 MDMs were used in English, while 2,986 MDMs were identified in Turkish. The comparison of the cumulative number of MDMs used in English (M = 3.12, SD = 3.65) and in Turkish (M = 2.99, SD = 5.11) did not reveal a statistically significant difference (t (1998) = 0.655, p = 0.513). The findings reveal a similar overall frequency of metadiscourse markers (MDMs) employed by the students in both their L1 Turkish and L2 English essays. This suggests a potential preference for using MDMs to fulfil similar functions across languages, such as organizing their discourse and establishing connections with both the text and the reader. Pre-intermediate proficiency may limit syntactic variation, leading to higher reliance on overt self-mentions. Furthermore, instruction in L2 writing may have emphasized transitions and frame markers more explicitly than affective strategies like attitude or engagement.

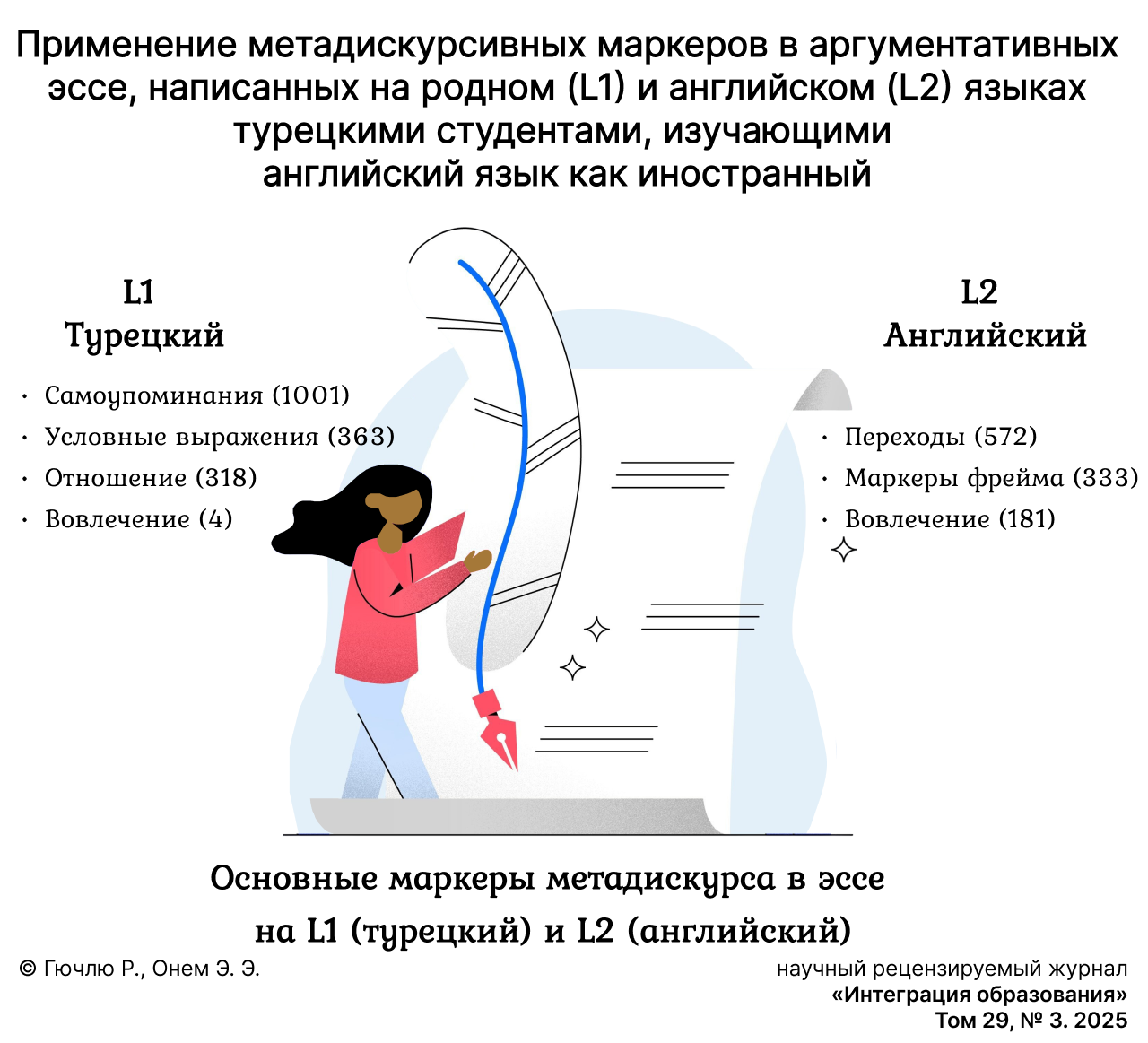

The analysis revealed the presence of all metadiscourse subcategories, encompassing both interactive (transitions, frame markers, evidentials, endophoric markers, and code-glosses) and interactional categories (hedges, boosters, attitude markers, engagement markers, and self-mentions), in essays written in both L1 Turkish and L2 English. Descriptive statistics further indicated a similar distribution pattern for these subcategories within the target text (TT) and essay text (ET) corpora. Furthermore, the data revealed a preference for specific MDM subcategories over others, with minimal disparity observed between the two language groups in their overall utilization. Specifically, in English argumentative essays, 572 markers were categorized as transitions, 333 as frame markers, 181 as code glosses, 6 as endophoric markers, and 5 as evidentials under the interactive metadiscourse category. Regarding interactional MDMs in English, 326 were hedges, 296 were boosters, 375 were attitude markers, 275 were engagement markers, and 747 were self-mentions. In Turkish argumentative essays, 334 MDMs were classified as transitions, 297 as frame markers, 123 as code glosses, 4 as endophoric markers, and 12 as evidentials. As for interactional MDMs in Turkish essays, the analysis revealed 363 hedges, 276 boosters, 318 attitude markers, 258 engagement markers, and 1,001 self-mentions. These results offer a comparative perspective on how Turkish EFL learners employ metadiscourse markers across languages. Figure visually represents this distribution pattern across L1 Turkish and L2 English essays.

F i g u r e. The distribution of interactive and interactional metadiscourse categories in L1 Turkish and L2 English

Source: Compiled by the authors.

As depicted in Figure, transitions, frame markers, and code glosses were identified as the most commonly used interactive categories in both corpora, whereas endophoric markers and evidentials were less frequently employed. Similar tendencies were observed in the use of interactional markers across both L1 and L2 essays. Turkish students consistently employed self-mentions, hedges, and attitude markers more frequently than boosters and engagement markers. Notably, self-mentions were the most frequently used interactional markers in both languages, though slightly more so in Turkish (L1). In contrast, engagement markers appeared more often in English (L2), suggesting greater audience awareness when writing in English.

The observed commonalities between the L1 Turkish and L2 English corpora, including the similar frequency of overall metadiscourse marker usage, the diversity of metadiscourse categories, the greater use of interactional categories compared to interactive categories and the similar distributional patterns of MDMs may be attributed to genre-specific factors. The findings of this study suggest that the demands of the argumentative essay genre may supersede the influence of native language (L1) or cultural background on metadiscourse marker usage. This aligns with M.M. Rahman’s [29] definition of genre as “the abstract, goal-oriented, staged, and socially recognized ways of using language delimited by communicative purposes, performed social interactions within rhetorical contexts, and formal properties”. The specific requirements of the argumentative essay genre might exert a stronger influence on language use, potentially leading to similar patterns in employing metadiscourse markers across languages. Furthermore, the observed similarities could be partially explained by the transfer of stylistic arrangement from L1 to L2 writing, as supported by previous research in contrastive rhetoric26 [30]. This prior knowledge of essay structure and argumentation strategies might influence students’ metadiscourse choices in both languages.

However, the higher frequency of interactive markers in L2 essays warrants further investigation. This could potentially be attributed to the participants’ educational background in L2 writing. Instruction in English essay writing might have instilled a stronger awareness and use of specific interactive markers compared to their L1 Turkish education. Additionally, the students’ concern about producing clear and well-structured L2 essays to demonstrate their writing proficiency might lead to a heightened focus on organizational markers.

Overall, the findings indicate that Turkish EFL learners employ all categories of metadiscourse in both languages, with comparable total frequencies. However, L2 essays contain slightly more interactive markers, especially transitions and frame markers, whereas L1 texts show a stronger tendency toward explicit authorial presence through self-mentions.

The discussion below delineates both the commonalities and disparities in the distributions and comparative outcomes about the usage of each metadiscourse category. These discussions are organized by the frequency of use within interactive and interactional categories, accompanied by examples extracted from each corpus.

Rather than discussing subcategories separately, we grouped findings under thematic lenses such as “stance construction” and “reader engagement.” For example, both self-mentions and attitude markers revealed how learners assert authorial presence, while transitions and frame markers were grouped under organizational awareness.

Results were reorganized under three macro-themes: Authorial Voice Construction, Genre Sensitivity and Text Organization, and L1 Cultural Transfer in L2 Writing. Each theme integrates several subcategories of MDMs for coherent interpretation.

Interactive Markers in L1 and L2 Essays. When the total of interactive MDMs was compared, it was seen that the number of interactive MDMs used in English was 1,097 and 770 for Turkish. Conversely, the combined count of interactional elements in essays written in L1 and L2 were 2,216 and 2,019, respectively. Statistical analysis indicates that the disparity between the quantity of interactional MDMs employed in English (M = 4.04, SD = 4.10) and Turkish (M = 4.43, SD = 6.62) was not statistically significant (t (998) = 1.131, p = 0.258). However, concerning the use of interactive MDMs, there is a significant difference (t (998) = 4.157, p < 0.001) between English essays (M = 2.19, SD = 2.84) and Turkish essays (M = 1.54, SD = 2.07) and more interactive MDMs were used in English than Turkish. This shows that students organized the discourse while writing their essays in L2 English. This finding regarding similar overall MDM use across L1 and L2 essays challenges the notion of a “native-speaker linguistic advantage” in academic writing proposed by Zao. This concept suggests native speakers hold a linguistic privilege due to their constant exposure to their mother tongue in both spoken and written contexts. Consequently, Zao implies a potential influence of native language status on metadiscourse use, with L2 writers facing difficulties in employing certain MDM elements. However, the present study does not support the inherent superiority associated with native-speaker status, leaving it a topic for further investigation. The observed higher frequency of interactive markers in L2 essays merits further exploration. A focus on text organization may be significant for L2 writers, as they strive for clear and coherent structure to ensure reader comprehension. Additionally, the educational background of the participants may play a role. Instruction in English essay writing might have instilled a stronger awareness and use of specific interactive markers compared to their L1 Turkish education. Finally, the potential influence of cultural context on MDM use warrants consideration. Shared cultural knowledge between the writer and reader in L1 writing might reduce the reliance on interactive markers to assist the readers, compared to the potentially unfamiliar cultural context in L2 writing.

Transitions. Transitions, defined as linguistic elements that connect various textual sections27, play a crucial role in argumentative essays by “linking arguments”28. As illustrated in figure, the analysis revealed transitions as the most frequently employed MDM subcategory. This finding suggests a potential preference among the students for constructing texts that prioritize authorial responsibility, as emphasized by J. Hinds29. The increased use of transitions by student writers can be further explained by their role in enhancing both coherence30 and cohesion [31] within sentences. This aligns with previous research by C. Can and F. Yuvayapan [20] and H.R. Djahimo [32] who observed a similar prevalence of transitions in student academic writing. When the number of the transition MDMs used in English (M = 5.72, SD = 3.28) and Turkish (M = 3.34, SD = 2.36) were compared, a statistically significant difference was found (t (198) = 5.893, p < 0.001), signaling using transitions more in English than in Turkish. This could show that students paid more attention in the organization of their L2 texts by using logical links between ideas. To further illustrate the use of transitions, exemplar sentences are provided from the two separate corpora.

1) “Using technology makes our lives easy. Furthermore, we use our technology to have fun“ (ENG–7).

2) “Uzaktaki arkadaşlarımizla kolaylikla iletişim kurabiliriz. Ayrıca, teknoloji istediğimiz her yere daha hizli ulaşmamizi sağlar“ (TR–89). “We can easily communicate with our distant friends. Additionally, technology allows us to get anywhere we want faster”.

In examples 1 and 2, transitions “furthermore” and “ayrıca” (furthermore) were used to make addition to support the previous argument with new information.

3) “My sister lives in İstanbul. I can’t see her but I can call her everyday because of technology“ (ENG–23).

4) “Sonuç olarak, teknolojiyi birçok nedenden dolayı kullanıyoruz ama ben bahsettiğim bu üç nedenin çok önemli olduğunu düşünüyorum“ (TR–6). “As a result, we use technology for many reasons but I think the three reasons I mentioned are very important”.

Both examples 5 and 6 showed that the students made use of transitions such as “but” and “ama” (but) to connect the previous sentence with a contrasting argument.

5) “Örneğin, bazı insanlar haberleri takip etmek için teknolojiyi kullanırlar“ (TR–64). “For example, some people use technology to keep up with the news“.

6) “We use technology to meet new friends“ (ENG–83).

Examples 3 and 4 used transitions to express the reasons. The students used “to” and “mAk için” (infinitive suffix -mAk (in order) to explain the reason for the action that is performed.

Frame Markers. Frame markers, broadly defined as linguistic elements that signal different stages within a text [13], play a significant role in argumentative essays. They function to “signal text boundaries or elements of the schematic text structure”31, enhancing reader comprehension by highlighting logical connections between ideas [33]. As depicted in figure, the analysis revealed that frame markers constituted the second most frequently employed interactive metadiscourse marker category across both subcorpora (L1 Turkish and L2 English essays). This indicates that students frequently employ frame markers to establish coherence in their essays. Additionally, no statistically significant differences were observed in the use of frame markers between English essays and Turkish essays (t (198) = 1.698, p = 0.091). Below are some examples of frame markers.

7) “There are a lot of reasons for using technology” (ENG–43).

8) “Teknolojiyi kullanmanın birçok nedeni vardır” (TR–16). “There are many reasons to use technology”.

9) “There are many advantages to using technology. First of all, people using technology meet new friends” (ENG–3).

10) “İkinci olarak, teknolojiyi gündemi takip etmek için kullanırız” (TR–75). “Second, we use technology to follow the agenda”.

11) “Sonuç olarak, teknolojiyi kullanmanın başlıca üç nedeni yukarıdakı gibidir” (TR–13). “As a result, the main reasons for using technology are like the ones mentioned above“.

12) “As conclusion, people are using technology for many reasons and technology is very useful for people” (ENG–5).

13) “In terms of the advantages of technology, we can talk about improvement in health sector” (ENG–12).

14) “İnternetin zamanı verimli kullanma açısından faydaları vardır” (TR–63). “The Internet has benefits in terms of using time efficiently”.

The analysis showed that the students employed frame markers with various functions, namely to announce the goals such as “there are a lot of reasons for…” in 7) and “nIn birçok nedeni vardır” (there are many reasons for…); to sequence the arguments with items such as “first of all” in 3) and “ikinci olarak” (secondly); to label stages of the discourse such as “sonuç olarak” (as a result) in 9) and “as conclusion” in 10), and to signal topic shift such as “in terms of” in 11) and “açısından” 12). These metadiscoursal items provide framing information about text boundaries and help for a good organizational structure of the discourse with a variety of functions.

Code-Glosses. Code-glosses, defined by W.J. Kopple32 as elements that “help readers grasp the appropriate meanings of elements in texts”, primarily aim to provide readers with supplementary information about concepts and ideas within a text. The analysis revealed that code-glosses were the third most frequent interactive metadiscourse marker category across both L1 Turkish and L2 English essays, as illustrated in figure. This finding aligns with D. Sancak’s33 observation of code-glosses ranking third behind transitions and frame markers in the opinion paragraphs written by L2 English novice writers. However, it is worth noting that the present study diverges from the findings of K. Hyland and P. Tse [2] and J.J. Lee and J.E. Casal [3] who reported a relatively low frequency of code-glosses in their analyses. A potential explanation for this discrepancy might lie in the differing academic disciplines investigated. While the current study focuses on argumentative essays centered on daily life experiences, J.J. Lee and J.E. Casal [3] study examined code-glosses within engineering texts. This suggests that the frequency of code-glosses may vary depending on the specific academic genre. Conversely, when comparing the mean number of code glosses used in English (M = 1.81, SD = 2.26) and Turkish (M = 1.23, SD = 1.76), another statistically significant difference emerged (t (198) = 2.029, p < 0.001), indicating that the utilization of code glosses is higher in English than in Turkish. The participants employed twice as many the number of code-glosses while writing in L2 English. The students might have presumed that their readers needed more guidance and more elaboration or specificity while reading their L2 English texts. Out of a concern for potential misinterpretation, English Teaching (ET) students may have frequently resorted to the utilization of code-glosses as a strategy to enhance clarity in their discourse. The findings suggest a potential link between code-gloss usage and the challenges associated with expressing ideas clearly in an L2. Students might utilize code-glosses more frequently in L2 essays due to a perceived need to ensure reader comprehension of their arguments. Conversely, the relative ease of expressing ideas in their L1 language might lead to a reduced reliance on code-glosses, potentially placing the burden of interpretation on the reader. Here are some illustrative examples of code-glosses from the two corpora:

15) “For example, we can communicate with our family members regardless of where we are” (ENG–7).

16) “Örneğin, benim en yakın arkadaşım iki sene önce İngilizce öğrendi ve İngiltere’ye gitti” (TR–94). “For example, my best friend learned English two years ago and went to England”.

17) “3.olarak teknolojiyi bilgi almak veya bilgi vermek için kullanırız (mesaj atarız, ararız)” (TR–62). “Thirdly, we use technology to get or give information (we text, call)”.

18) “Using technology makes life easy (computer, phone, tablet, watch, car…)” (ENG–7).

As it can be seen in the examples above, the participants used code glosses to clarify an argument through exemplification, as seen with “for example” in 15) and “örneğin” (for example) in 16), as well as reformulation, illustrated by “veya” (or) in 17), and the use of parentheses in 18). Establishing connections with preceding concepts, these resources facilitate coherence among elements throughout the reading process, thereby enhancing the accessibility and reader-friendliness.

Endophoric Markers. Endophoric markers, defined by K. Hyland34 as “expressions which refer to other parts of the text”, play a vital role in guiding reader comprehension by establishing connections within the text. However, the analysis revealed a relatively low frequency of endophoric markers within both L1 Turkish and L2 English essay corpora. This finding suggests a potential influence of genre on metadiscourse marker usage. Compared to argumentative essays, academic genres such as research articles may necessitate a higher frequency of endophoric markers. The writers of research articles often integrate results presented in tables, figures, or previous sections, requiring them to employ endophoric markers to guide readers through the interconnected information. In terms of endophoric marker, the analysis also indicates no significant differences between L1 and L2 texts (t (198) = 0.587, p = 0.558). Here are some examples of endophoric markers from the two corpora.

19) “Teknolojiyi kullanmanin faydalari yukarıdakı gibidir” (TR–68). “The benefits of using technology are as above”.

20) “I use technology for the reasons above” (ENG–56).

In example 9), the author makes reference to a previous argument mentioned within the text using “yukarıdakı” (above) in 19) and “above” in 20). In this study, endophoric markers were observed to be utilized solely to reference previous arguments in the text, rather than referring to subsequent parts. These tools are predominantly employed in scientific texts since they present facts, theoretical concepts, methodology, and findings described within the body of the text [2].

Evidentials. As defined by K. Hyland35, evidentials are “expressions that refer to information from other texts”. In a broader sense, they function as linguistic markers indicating references to external sources. Consistent with the argumentative nature of the essays analyzed, evidentials emerged as one of the least frequently employed metadiscourse markers within both L1 Turkish and L2 English corpora, as illustrated in figure. This finding aligns with expectations, as argumentative essays typically place less emphasis on external sources compared to research-oriented genres such as research papers, dissertations, or theses36 [34]. The focus on establishing arguments and claims in these student essays reduces the need for extensive referencing, particularly within the introduction and literature review sections where evidentials are more commonly used to acknowledge prior research37. Additionally, no statistically significant difference was observed (t (198) = 1.333, p = 0.184) between the number of evidentials used in English (M = 0.05, SD = 0.26) and Turkish (M = 0.12, SD = 0.46). To illustrate the limited use of evidentials within the corpora, the following examples showcase the few instances where they were identified in the student essays.

21) “Çalışmalar, teknolojinin pek çok hastalığın tanı ve tedavisinde kullanildığını göstermektedir” (TR–17). “Studies show that technology is used in the diagnosis and treatment of many diseases”.

22) “Previous studies show that technology provides new treatments for many diseases” (ENG–87).

The examples provided, such as “çalışmalar” (the studies) in 21) and “previous studies show that” in 22), serve as evidence for a given statement, indicating that students aim to demonstrate the reliability and credibility of their arguments to their readers.

Interactional Markers in L1 and L2 Essays. The intralinguistic comparative analyses showed that the difference between interactive (M = 2.19, SD = 2.84) and interactional (M = 4.04, SD = 4.10) MDMs used in texts written in L2 English was statistically significant. Interactional MDMs were used more than interactive MDMs in English (t (998) = 8.259, p < 0.001). Likewise, the difference between the means of interactive (M = 1.54, SD = 2.07) and interactional (M = 4.43, SD = 6.62) MDMs used in texts written in L1 Turkish was statistically significant as well (t (998) = 9.324, p < 0.001) and it was seen that more interactional MDMs were used in Turkish texts. This intralinguistic examination revealed that Turkish students were more inclined towards establishing interaction with their audience rather than directing their readers to convey their viewpoints and attitudes, and involving the reader in the text, irrespective of the linguistic context in which the essays were produced. In simpler terms, engaging with the readers in L1 and L2 English heavily relies on features that signal the writers’ position as authors.

Self-Mentions. The analysis revealed self-mentions, defined as markers where the writer refers to themselves to establish reader engagement with their perspective38 [2], as the most frequently used interactive metadiscourse category across both L1 Turkish and L2 English essays, as depicted in figure. This suggests that students assert their authorial persona by expressing their strong beliefs and ideas through self-mentions in both their native and second language essays. Similarly, M.M. Zali et al. [35] analyzed the evaluative essays by undergraduate L2 English students concerning interactive and interactional categories and found out the prominent feature is self-mention. It could be because of the type of text as it has an influence on the type of metadiscourse used39 as the students put forth their arguments and ideas by conveying their authorial persona. Also, the number of self-mentions used in English (M = 7.47, SD = 5.99) and Turkish (M = 10.01, SD = 6.37) showed a statistically significant difference (t (198) = 2.906, p < 0.005). The higher use of self-mention in Turkish could be attributed to the agglutinative and pro-drop nature of the Turkish language. Conversely, the prevalence of self-references in L2 English may stem from the growing endorsement of “I” within the contemporary English academic environment.

The prominence of self-mentions, particularly in Turkish, may reflect a cultural tendency toward explicit authorial voice, contrasting with Anglophone norms where hedging is often preferred. This suggests that learners might carry over L1 rhetorical habits into L2 writing unless explicitly trained otherwise. Unlike findings from Chinese EFL learners [30], who underuse self-mentions due to collectivist norms, Turkish learners in this study frequently referenced themselves, possibly reflecting national educational writing practices.

The following are examples from the two sets of corpora.

23) “Örneğin, okula genellikle otobüsle giderim” (TR–4). “For example, I usually take the bus to the school”.

24) “For example, in the summer, I played video games with my friends and I had new friends from Giresun” (ENG–4).

The examples above showed that the students referred to themselves with first person singular verbal suffix “-(I)m” in 23) and with first-person singular pronouns such as “I” in 24).

Attitude Markers. Attitude markers, as defined by K. Hyland, function to express the writer’s subjective viewpoints and stances on the discussed content, differing from markers of epistemic certainty. These markers allow writers to convey a range of personal feelings, including surprise, agreement, importance, obligation, or frustration. The analysis revealed that attitude markers constituted another frequently used interactive metadiscourse category within both L1 Turkish and L2 English essays (Figure). This finding suggests a tendency among the students to directly express their attitudes towards the arguments presented, potentially reflecting a more personal engagement with the writing task. Moreover, the frequent use of attitude markers underscores the prevalence of emotional perception in their academic writing. No statistically significant difference was found between the number of attitude markers used in English (M = 3.75, SD = 3.05) and Turkish (M = 3.18, SD = 2.11, t (198) = 1.538, p = 0.570). Below are some examples of attitude markers from both corpora.

25) “Son olarak, en sevdiğim yönlerinden biri olan bilgisayar oyunları, sanal gerçeklik vs. ınsanları eğlendiren teknolojik gelişmeler gün sonunda stres atmamızı sağlar” (TR–1). “Last but not least, one of my favorite aspects, computer games, virtual reality, etc. technological advances that entertain people allow us to relieve stress at the end of the day”.

26) “Playing computer games is my favorite activity since 2019” (ENG–10).

It is obvious that attitude markers such as “...sevdiğim …” (...that I like …) in 25) and “my favorite…” in 26) convey the students’ personal feelings.

Hedges. Consistent with K. Hyland’s40 observation that hedges indicate “plausible reasoning rather than certain knowledge”, the analysis revealed hedges as a frequently employed interactive metadiscourse category across both L1 Turkish and L2 English essays (Figure). Furthermore, a statistical comparison of hedge usage between the English (M = 3.26, SD = 2.75) and Turkish (M = 3.63, SD = 10.93) corpora did not yield a statistically significant difference (t (198) = 0.328, p = 0.743). This suggests that students in both language groups displayed a similar tendency to utilize hedges when expressing arguments in their essays. These findings suggest that students exercise caution and modesty when expressing their views on the topic. The following examples of hedges are drawn from the two sub-corpora:

27) “Üçüncü olarak, insanlar daha uzun ve sağlıklı yaşamak ister” (TR–8). “Third, people want to live more and healthy”.

28) “People use technology for many reasons and technology is very useful for people” (ENG–13).

29) “Örneğin, ben genellikle okula otobüs ile giderim” (TR–77). “For example, I usually go to school by bus”.

30) “I sometimes go to university by bus” (ENG–26).

31) “Teknolojinin gelecekte daha pek çok faydasının olacağı kanaatindeyim” (TR-35). “I believe that technology will have many more benefits in the future”.

32) “I think that technology is useful for us” (ENG–51).

33) “Teknolojinin dezavantajlarından sıklıkla bahsederler, teknolojinin çeşitli faydalarından yararlanmıyor olabilirler” (TR–93). “They often talk about the disadvantages of technology, they may not benefit from the various benefits of technology”.

34) “Some people may not follow technological improvements and so they are not aware of good sides” (ENG–18).

In the given examples, hedges were employed to foster solidarity and to mitigate the assertiveness and directness inherent in the asymmetrical relationship with the readers, as seen with the use of the epistemic pronoun “insanlar” (human beings) as a mass noun in 27) and 28); with epistemic adjectives such as “many” in 28), “pekçok” (many) in 31), “çeşitli” (various) in 33) and “some” in 34); with epistemic adverbs such as “genellikle” (usually) and “sometimes” in 29) and 30) respectively; with epistemic lexical verbs such as “kanaatinde ol-” (consider) in 31) and “to think” in 32); with epistemic modal suffixes such as “(I)yor ol+Abil+Ir/lAr” (IMPF AUX-PSB-AOR-3SG/3PL) in 33) and “may not” in 24). It could be understood that there are various realizations of hedges used by the students both in their L1 and L2 essays. All these epistemic expressions help the readers modulate claims by anticipating readers’ responses to the students’ statements. Accordingly, the students build writer-reader relationships with the use of these interactional strategies. K. Hyland41 cites numerous studies indicating that hedges rank among the most common interactional metadiscourse strategies in academic discourse.

Boosters. Boosters function to present certainty regarding the arguments presented, minimizing opportunities for reader disagreement42. The analysis revealed that boosters, while employed less frequently than other interactional markers, were still present in student essays from both L1 Turkish and L2 English corpora (Figure). Interestingly, the statistical comparison (t (198) = 0.696, p = 0.487) between the use of boosters in English (M = 2.96, SD = 1.93) and Turkish (M = 2.76, SD = 2.13) essays did not yield a significant difference. Some instances of boosters from the corpora are presented below.

35) “Çünkü, teknoloji sayesinde her şey gelişir (araba, telefon, bilgisiyar, tablet, saat…)” (TR–9). “Because, thanks to technology, everything develops (cars, telephone, computer, tablet, watch…)”.

36) “Everybody should take good advantage of technology” (ENG–56).

37) “For example, in the old days we did not use the telephone. We use letter, telegraphs…and this is such a long process” (ENG–9).

38) “Teknolojinin hayatımız için son derece faydalı yönleri vardir” (TR–43). “Technology has extremely beneficial aspects for our lives.”

39) “It is clear that telephones make our lives easy” (ENG–8).

40) “I develop myself by means of technology. I especially like self-development online education” (ENG–59).

41) “I must wake up earlier than 6.00 o’clock use the internet to find some online educational sources” (ENG–34).

42) “Arkadaşlarımla sosyal medya üzerinden sohbet etmek bana hep iyi gelmiştir” (TR–97). “Chatting with my friends on social media has always been good for me.”

The aforementioned examples showcase the various ways in which students utilize boosters within both L1 Turkish and L2 English essays. The analysis of the corpora revealed boosters appearing in several forms, including:

Universal pronouns: “her şey” (everything) in 35) and “everybody” in 36).

Amplifiers: “such” in 37) and “son derece” (extremely) in 38), intensifying the meaning of adjectives or verbs.

Emphatics: “clear” in 39) and “especially” in 40), adding emphasis to arguments and potentially conveying certainty.

Modal auxiliaries and suffixes: “must” in 41) and “-mIş+Dir” (PRF-COP-3SG) in 42), expressing certainty.

These diverse booster applications serve to potentially strengthen the persuasiveness of the writers’ viewpoints and bolster the validity of their arguments within their essays.

Engagement Markers. Engagement markers, defined by K. Hyland43 as mechanisms to directly involve the reader, emerged as a relatively infrequent subcategory within the metadiscourse markers identified in both L1 Turkish and L2 English essays (Figure). This finding aligns with previous research by K. Hyland44 [34] and J.J. Lee and J.E. Casal [3], both of which reported a similar scarcity of engagement markers in their analyses. The observed limited use of engagement markers might be attributed to the inherent characteristics of argumentative essays, which often prioritize presenting information and arguments in a more objective and formal style, potentially minimizing the need for direct reader interaction. Furthermore, the statistical comparison (t (198) = 0.704, p = 0.170) revealed no significant difference in engagement marker use between L2 English essays (M = 2.75, SD = 3.61) and L1 Turkish essays (M = 2.58, SD = 3.47). Taken from two corpora, the following examples illustrate engagement markers.

43) “İnsanlar günümüzde teknolojiyi her alanda çok fazla kullanir” (TR–9). “People in our time use technology extensively in every field”.

44) “We are using technology for some reasons” (ENG–2).

45) “Birincisi, yeni arkadaşlar edinebilirsin bu sayede yeni dil öğrenebilirsin” (TR-38). “First, you can make new friends so you can learn a new language”.

46) “You can also play computer games on the Internet” (ENG–98).

The examples 43) and 44) drew on resources such as “-(I)mIz”, (first person plural possessive suffix), and “we” respectively, which function as inclusive “we” to include the readers directly in the argument. According to Fu and K. Hyland, “common ground” and “solidarity” with the reader can be established with the use of “we”. This suggests that students might utilize inclusive language to develop a sense of shared social identity with the reader, potentially contributing to the social construction of their arguments within the essays. The analysis also revealed the presence of reader pronouns, such as “-in/-niz” (second person singular suffix) in Turkish and “you” in English (see examples 45 and 46), functioning as engagement markers. These markers directly address the reader, fostering a connection between the writer and the audience. By potentially drawing readers into the text, such engagement markers might mitigate objections to the writer’s claims.

Overall, this study found that Turkish EFL learners employ a comparable range of metadiscourse markers in both their L1 and L2 argumentative writing, though the distribution of specific categories varies. Interactive markers were used more frequently in L2 English texts, while interactional markers (especially self-mentions) were more prominent in L1 Turkish compositions. The dominance of self-mentions in L1 may reflect greater rhetorical confidence or cultural norms favoring explicit authorial presence. The heavier use of transitions in L2 may result from instructional training in text structuring in English classes. The underuse of attitude markers may indicate limited lexical or rhetorical repertoire at the pre-intermediate level. These results partially align with K. Hyland45, who noted that EFL writers often rely on interactional markers in personal writing. However, in contrast to studies involving Chinese EFL learners [36], our Turkish participants used more interactive devices in L2 writing, perhaps reflecting local curricular emphasis on cohesion and coherence. The findings suggest that genre conventions and classroom instruction may play a more decisive role in shaping metadiscourse use than language background alone. This supports genre-based approaches to writing instruction that emphasize rhetorical function over linguistic form. From a pedagogical standpoint, the observed imbalance in interactional features indicates a need to develop learners’ capacity to engage readers and project stance in L2 writing. Indeed, the findings indicate that Turkish EFL learners employ all categories of metadiscourse in both languages, with comparable total frequencies. However, L2 essays contain slightly more interactive markers, especially transitions and frame markers, whereas L1 texts show a stronger tendency toward explicit authorial presence through self-mentions.

Discussion and Conclusion

Comparison with Previous Research. The present study examined the use of metadiscourse markers in L1 Turkish and L2 English argumentative essays written by the same group of pre-intermediate EFL learners. Using K. Hyland’s Interpersonal Model, the analysis identified both shared tendencies and notable differences in the distribution and functions of interactive and interactional markers across the two corpora.

A central finding was the broadly comparable overall frequency of metadiscourse markers in L1 and L2 texts, which suggests that genre requirements exert a strong influence on metadiscourse use regardless of language. This supports previous observations that argumentative writing imposes structural and rhetorical demands that promote the use of organizational and stance-related devices46 [3]. The predominance of interactional resources in both languages is consistent with genre-driven emphasis on persuasion, a finding echoed in studies of argumentative essays in other EFL contexts [7; 8].

At the same time, statistically significant differences emerged in the use of interactive markers, particularly transitions and frame markers, which were more frequent in L2 English essays. This pattern may reflect explicit instruction in cohesion and coherence in the local EFL curriculum, an interpretation consistent with research showing that pedagogical emphasis can directly shape learners’ rhetorical choices [4; 10]. By contrast, Chinese EFL learners in D. Liu [36] study relied less on interactive devices and more on stance markers, highlighting the role of instructional traditions and curricular priorities in shaping metadiscourse distribution.

The high frequency of selfmentions in L1 Turkish essays, and their persistence in L2 English writing, points to crosslinguistic transfer of rhetorical habits. The prodrop and agglutinative nature of Turkish facilitates selfreference, and cultural norms in Turkish academic writing may legitimize more overt authorial presence. These findings align with the view that L1 rhetorical conventions can influence L2 production even when learners are exposed to different target norms [18]. As noted by E. Tikhonova and L. Raitskaya [37], the ways in which authors present themselves in academic texts are shaped by disciplinary expectations and national academic cultures, and such positioning conventions tend to transfer across languages. This may explain why Turkish learners maintain similar selfmention patterns in L2 writing despite exposure to alternative Anglophone norms.

While both corpora showed substantial use of interactional markers, engagement devices remained relatively underused, particularly in L2 writing. This echoes findings from multiple EFL contexts where novice writers struggle to incorporate reader-oriented strategies [6; 8]. Such underuse suggests a need for targeted instruction that moves beyond structural cohesion to include dialogic engagement, thereby fostering audience awareness and reader – writer interaction.

The results demonstrate that L1/L2 similarities in metadiscourse use are shaped by genre conventions, but differences emerge in marker distribution due to instructional focus, cultural rhetorical norms, and language-specific affordances. The findings also highlight the pedagogical value of explicitly addressing underrepresented categories such as engagement markers and of training learners to balance hedging and boosting to achieve rhetorical flexibility.

This study investigated how Turkish pre-intermediate EFL learners employ metadiscourse markers in L1 and L2 argumentative essays, drawing on K. Hyland’s47 Interpersonal Model to compare interactive and interactional resources. The findings indicate that while the overall frequency of metadiscourse markers was similar across languages, there were meaningful differences in their distribution. L2 English essays contained more interactive markers, particularly transitions and frame markers, wherea L1 Turkish essays featured more frequent self-mentions.

These results contribute to the understanding of how genre requirements, instructional practices, and academic culture jointly influence metadiscourse use. The study offers practical implications for EFL pedagogy. Teachers should guide learners in using self-mentions appropriately in L2 academic contexts, diversify their engagement strategies, and maintain a balanced use of interactive and interactional markers. Incorporating corpus-informed examples into instruction can help learners develop rhetorical awareness and audience-sensitive writing skills.

The study has several limitations. It examined only argumentative essays, which restricts the generalizability of the findings to other academic genres. The participant sample was limited to one proficiency level and institutional context, and topic familiarity was not systematically controlled. Future research should include multiple genres, varied proficiency levels, and broader institutional representation. Including a native English L1 control group would allow for more nuanced cross-linguistic comparisons.

Overall, this research advances the discussion of L1 and L2 metadiscourse use by highlighting the combined influence of genre, instructional context, and cultural rhetorical norms. By addressing the areas identified for pedagogical intervention, EFL curricula can better prepare learners to produce rhetorically balanced, coherent, and reader-oriented academic texts in both their native and target languages.

1 Hyland K. Metadiscourse: Exploring Interaction in Writing. New York: Continuum; 2005.

2 Vande Kopple W.J. Some Exploratory Discourse on Metadiscourse. College Composition and Communication. 1985;36(1):82–93. https://doi.org/10.2307/357609; Crismore A., Markkanen R., Steffensen M.S. Metadiscourse in Persuasive Writing: A Study of Texts Written by American and Finnish University Students. Written Communication. 1993;10(1):39–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088393010001002; Hyland K. Metadiscourse: Exploring Interaction in Writing; Ädel A. Metadiscourse. In: The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons; 2013. p. 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal0763

3 Vande Kopple W.J. Some Exploratory Discourse on Metadiscourse.

4 Crismore A., Markkanen R., Steffensen M. Metadiscourse in Persuasive Writing: A Study of Texts Written by American and Finnish University Students.

5 Hyland K. Metadiscourse: Exploring Interaction in Writing.

6 Ibid.

7 Alqahtani N. Metadiscourse Markers in English Academic Writing of Saudi EFL Students and UK L1 English Students. Cardiff University; 2022.

8 Algi S. Hedges and Boosters in L1 and L2 Argumentative Paragraphs: Implications for Teaching L2 Academic Writing. Middle East Technical University; 2012. (In Turk., abstract in Eng.) Available at: http://etd.lib.metu.edu.tr/upload/12614579/index.pdf (accessed 20.04.2025); Bayyurt Y. Hedging in L1 and L2 Student Writing. In: Kincses-Nagy E. (eds) Proceedings of the 15th International Conference of Turkish Linguistics. Szeged: Szeged University Press; 2012. p. 123–132. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/2565607/Hedging_in_L1_and_L2_student_writing_A_case_in_Turkey (accessed 20.04.2025).

9 Can H. [An Analysis of Freshman Year University Students’ Argumentative Essays]. Boğaziçi University; 2006. (In Turk.) Available at: https://tezara.org/theses/188963 (accessed 20.04.2025).

10 Galtung J. Structure, Culture, and Intellectual Style: An Essay Comparing Saxonic, Teutonic, Gallic and Nipponic Approaches. Social Science Information. 1981;20(6):817–856. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901848102000601; Myers G. The Pragmatics of Politeness in Scientific Articles. Applied Linguistics. 1989;10(1):1–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/10.1.1

11 Vande Kopple W.J. Some Exploratory Discourse on Metadiscourse; Crismore A., Markkanen R., Steffensen M. Metadiscourse in Persuasive Writing: A Study of Texts Written by American and Finnish University Students; Hyland K. Metadiscourse: Exploring Interaction in Writing; Ädel A. Metadiscourse.

12 Vande Kopple W.J. Some Exploratory Discourse on Metadiscourse.

13 Crismore A., Markkanen R., Steffensen M. Metadiscourse in Persuasive Writing: A Study of Texts Written by American and Finnish University Students.

14 Hyland K. Metadiscourse: Exploring Interaction in Writing.

15 Alqahtani N. Metadiscourse Markers in English Academic Writing of Saudi EFL Students and UK L1 English Students. Cardiff University; 2022.

16 Algi S. Hedges and Boosters in L1 and L2 Argumentative Paragraphs: Implications for Teaching L2 Academic Writing; Bayyurt Y. Hedging in L1 and L2 Student Writing.

17 Can H. [An Analysis of Freshman Year University Students’ Argumentative Essays].

18 Galtung J. Structure, Culture, and Intellectual Style: An Essay Comparing Saxonic, Teutonic, Gallic and Nipponic Approaches; Myers G. The Pragmatics of Politeness in Scientific Articles.

19 Hyland K. Metadiscourse: Exploring Interaction in Writing.

20 Ibid.

21 Vande Kopple W.J. Some Exploratory Discourse on Metadiscourse; Crismore A., Markkanen R., Steffensen M. Metadiscourse in Persuasive Writing: A Study of Texts Written by American and Finnish University Students.

22 Hyland K. Metadiscourse: Exploring Interaction in Writing.

23 Vazquez-Orta I., Lafuente-Millan E., Lores-Sanz R., Mur-Duenas M.P. How to Explore Academic Writing from Metadiscourse as an Integrated Framework of Interpersonal Meaning: Three Perspectives of Analysis. In: Alastrúe R., Pérez-Llantada C., Neumann C.P. (eds) Proceedings of the 5th AELFE Conference. Zaragoza: Universidad de Zaragoza; 2006. p. 197–208.

24 Hyland K. Metadiscourse: Exploring Interaction in Writing.

25 Ibid.

26 Hinds J. Reader versus Writer Responsibility: A New Typology. In: Connor U., Kaplan R. (eds) Writing Across Languages: Analysis of L2 Texts. Boston: Addison-Wesley; 1987. p. 141–152; Kaplan R.B. Cultural Thought Patterns in Inter-Cultural Education. Language Learning. 1966;16(1–2):1–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-1770.1966.tb00804.x; Mauranen A. Contrastive ESP Rhetoric: Metatext in Finnish-English Economics Texts. English for Specific Purposes. 1993;12(1):3–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/0889-4906(93)90024-I; Valero-Garcés C. Contrastive ESP Rhetoric: Metatext in Spanish-English Economics Texts. English for Specific Purposes. 1996;15(4):279–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-4906(96)00013-0

27 Hyland K. Metadiscourse: Exploring Interaction in Writing. p. 204.

28 Hyland K. Metadiscourse: Exploring Interaction in Writing.

29 Hinds J. Reader versus Writer Responsibility: A New Typology.

30 Duke C.R. Writing through Sequence: A Process Approach. Boston: Little, Brown and Company; 1983.

31 Hyland K. Metadiscourse: Exploring Interaction in Writing.

32 Vande Kopple W.J. Some Exploratory Discourse on Metadiscourse. p. 84.

33 Sancak D. The Use of Transitions, Frame Markers and Code Glosses in Turkish EFL Learners’ Opinion Paragraphs. Middle East Technical University; 2019. Available at: https://etd.lib.metu.edu.tr/upload/12624312/index.pdf (accessed 20.04.2025).

34 Hyland K. Metadiscourse: Exploring Interaction in Writing. p. 60.

35 Ibid. p. 58.

36 Hyland K. Metadiscourse: Exploring Interaction in Writing.

37 Ibid.

38 Ibid.

39 Crismore A., Farnsworth R. Metadiscourse in Popular and Professional Science Discourse. In: Nash. W. (eds) The Writing Scholar: Studies in Academic Discourse. Newsbury Park: Sage. 1990. p. 118–136.

40 Hyland K. Talking to Students: Metadiscourse in Introductory Course Books. English for Specific Purposes. 1999;18(1):3–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-4906(97)00025-2

41 Hyland K. Metadiscourse: Exploring Interaction in Writing.

42 Ibid.

43 Ibid.

44 Ibid.

45 Hyland K. Metadiscourse: Exploring Interaction in Writing.

46 Hyland K. Metadiscourse: Exploring Interaction in Writing.

47 Ibid.

Об авторах

Рухан Гючлю

Газиантепский университет

Автор, ответственный за переписку.

Email: gucluruhan@gmail.com

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2748-8363

Scopus Author ID: 57220577363

доктор философии, ассоциированный профессор департамента английского языка и литературы факультета науки и искусств

Турция, 27310, г. Газиантеп, Университетский бульвар, д. 316Энгин Эврим Онем

Университет Эрджиес

Email: eonem@erciyes.edu.tr

ORCID iD: 0000-0002-2711-7511

Scopus Author ID: 55749679300

доктор философии, преподаватель департамента базового английского языка Школы иностранных языков

Турция, 38020, г. Кайсери, ул. Турхана Байтопа, д. 1Список литературы

- Jones J.F. Using Metadiscourse to Improve Coherence in Academic Writing. Language Education in Asia. 2011;2(1):1–14. Available at: https://researchprofiles.canberra.edu.au/en/publications/using-metadiscourse-to-improve-coherence-in-academic-writing (accessed 20.04.2025).

- Hyland K., Tse P. Metadiscourse in Academic Writing: A Reappraisal. Applied Linguistics. 2004;25(2):156–177. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/25.2.156

- Lee J.J., Casal J.E. Metadiscourse in Results and Discussion Chapters: A Cross-Linguistic Analysis of English and Spanish Thesis Writers in Engineering. System. 2014;46:39–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2014.07.009

- Sun S.A., Jiang F. Analyzing Metadiscourse in L2 Writing for Academic Purposes: Models and Approaches. Research Methods in Applied Linguistics. 2024;3(3):100149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmal.2024.100149