Описание культурного шока китайскими студентами, обучающимися в России: качественный и количественный анализ

- Авторы: Рюмшина Л.И.1, де Оливейра Д.Л.2

-

Учреждения:

- Южный федеральный университет

- Федеральный университет Рио-де-Жанейро

- Выпуск: Том 29, № 3 (2025)

- Страницы: 542-554

- Раздел: Педагогическая психология

- Статья получена: 10.05.2025

- Статья одобрена: 24.07.2025

- Статья опубликована: 22.09.2025

- URL: https://bakhtiniada.ru/1991-9468/article/view/291162

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.15507/1991-9468.029.202503.542-554

- EDN: https://elibrary.ru/iigbxy

- ID: 291162

Цитировать

Полный текст

Аннотация

Введение. Рост числа студентов, получающих образование за рубежом, оказывает влияние на экономику, а изучение их социокультурной адаптации, в том числе и культурного шока как ее неотъемлемой части, актуализируется в результате стремления стран повысить свою конкурентоспособность для привлечения иностранных обучающихся. Однако проблемы, вызывающие культурный шок в неанглоязычных странах, в том числе проявление культурного шока у азиатских студентов, не получили должного внимания со стороны ученых. Цель исследования – изучить культурный шок среди китайских студентов, обучающихся в России.

Материалы и методы. Осуществлен качественно-количественный анализ описаний культурного шока 82 китайскими студентами, обучающимися в российском университете. Независимость между переменными, а также их связь проверялась путем обработки результатов на основе программы «R» с проведением теста хи-квадрат, теста Крамера V. Статистическая значимость внутри групп и между ними измерялась с помощью биномиального теста, z-критерия и дисперсионного анализа (ANOVA).

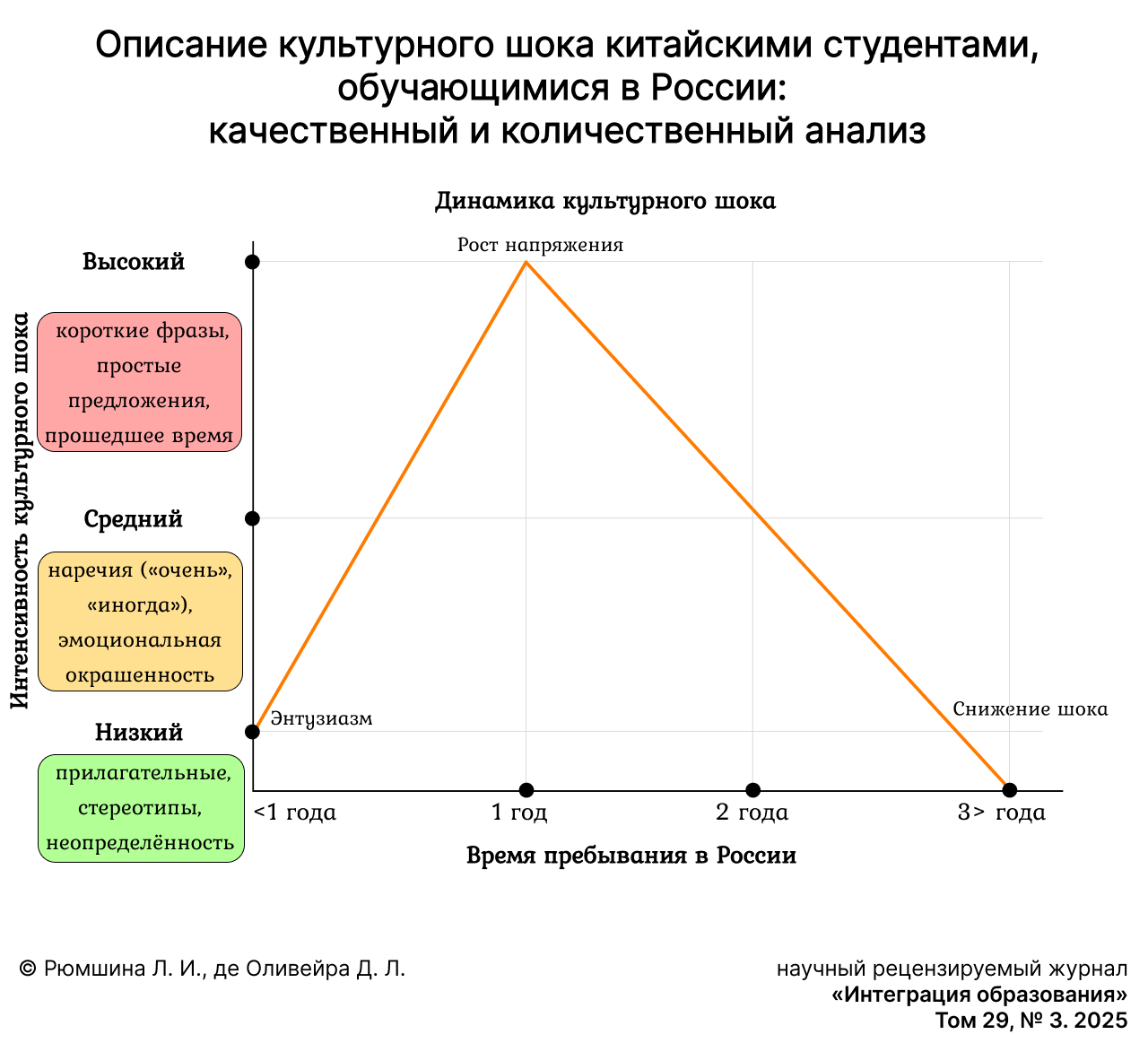

Результаты исследования. Уровень выраженности культурного шока меняется в зависимости от времени пребывания обучающихся в иной культуре. Описания студентов, испытавших культурный шок, отличаются простотой и конкретностью изложения проблемы. Характеристики ситуаций, вызвавших низкий культурный шок, являются формальными, отражают распространенные мнения и стереотипы, а также неуверенность в социокультурной адаптации.

Обсуждение и заключение. Проведенное исследование расширяет и конкретизирует представление о культурном шоке. Подтверждается зависимость культурного шока от времени пребывания иностранных студентов в другой стране, а также его неоднозначная оценка. Несмотря на то, что исследование основывалось на позициях китайских студентов, достигнутые результаты могут быть приняты во внимание при изучении социокультурной адаптации обучающихся различных национальностей.

Полный текст

Introduction

Culture shock as a consequence of anxiety that results from losing all our familiar signs and symbols of social intercourse1, is an integral part of sociocultural adaptation [1; 2]. In essence, culture shock is a conflict between two cultures at the level of individual consciousness. Therefore, the “return” to ones culture can also result in a “reverse” culture shock [3].

Although culture shock can also have some positive effects [4], like any conflict, introduction into a new culture causes very unpleasant experiences for a person. These experiences differ depending on the factors facilitating or complicating the adaptation and the time spent in a different culture [5]. Thus, culture shock can be considered as a psychological phenomenon, the intensity of which may change as a person adapts to new conditions. Despite attempts to overcome the shortcomings of K. Obergs concept of culture shock [6], the stages he identified are still the best known.

According to K. Oberg, the first stage, which ends quickly, is characterized by enthusiasm, high spirits, and high hopes. During this period, the individual evaluates the differences between “their own” and the “new” cultures with great interest. The second stage, according to K. Oberg, involves a hostile and aggressive attitude towards the host country. This crisis stage results from a non-objective analysis of the current situation. Problems arise when communicating with the new culture. As a result, the person becomes hostile towards those representatives, considering that this discomfort occurs because of them. At the third stage, depression slowly gives way to a feeling of confidence and satisfaction. The person feels more adapted and integrated into social life. Finally, the fourth stage is characterized by adapting to the new culture and understanding its traditions and habits. The person feels more confident and relaxed when interacting with local people. As K. Oberg believed, until a person reaches a level of adaptation that satisfies them, they cannot become a full-fledged member of society since they are “sick” with the symptoms of culture shock2.

Naturally, people will experience culture shock differently, even when staying at the same stage. It is related to many factors, objective and subjective. The former, as a rule, include cultural distance, i. e., the degree of differences between “ones own” and “foreign” cultures, the presence or absence of conflicts between these countries in the present and the past, the socio-economic conditions of the host country, the tolerance of residents towards visitors, and others.

Even factors independent of a person are perceived differently depending on a persons age, gender, level of education, and personal qualities. For example, with age, a person finds it more challenging to integrate into a new cultural environment, and experiences culture shock more intensely and for a more extended period, and the higher the level of education, the more successful the adaptation is. In literature, one can find descriptions of numerous personal characteristics that, to the certain extent, contribute to sociocultural adaptation and overcoming culture shock [7; 8]. A person’s life experience also helps, together with their motivation to move, previous experience of staying in another culture, and so on. In addition, sociocultural and subjective factors of expatriate adjustment are widely discussed [5; 9], but there is a lack of research regarding their interdependence, especially in the Asian context [10]. This also concerns international students. One can agree with some authors that the literature on international students is more eclectic and diverse than on expatriates and migrants [11]. This significantly complicates the development of a general direction for its analysis.

The aim of this research is to investigate how culture Shock is experienced and described by Chinese students studying in Russia, contributing to filling a gap that is observed in this field of studies.

Literature Review

In modern conditions, the number of students obtaining education abroad constantly increases [12; 13]. They have a growing significant economic and cultural impact [14], and countries strive to enhance their competitiveness to attract international students and gain a substantial market share [15; 16].

While the number of international students is growing, the number of publications addressing their issues increase as well [2; 17]. According to the analysis of published studies on the problems of international students from 2002 to 2022 by O. Oduwaye et al., the USA is the largest producer of such research, followed by Australia, the UK, and Canada [13]. Surprisingly, when analyzing most European countries, there is a need for more research on this topic compared to the English/speaking countries.

However, Europe remains a popular destination for non-English-speaking international students, with countries like France, Russia, and Germany on the top of this list [18]. The same applies to non-European countries such as Turkey, China, and Malaysia. Notably, the results show no significant differences concerning the academic problems faced by international students in English-speaking countries versus non-English-speaking countries [13].

Some sociocultural adaptation issues faced by international students are predictable, but there can also exist more unexpected ones that largely trigger culture shock. According to L. Tang and C. Zhang, along with cultural intelligence, these issues represent new scientific topics in analyzing issues faced by international students [12]. As a rule, all subjects discussed in literature, regardless of the students country of origin or the host country, can be subdivided into four categories: academic, sociocultural, psychological, and economic [19]. These issues remained unchanged from 2002 to 2022 [13].

The most common stress-inducing issues international students face in their host countries, especially in the first and second years after arrival, are sociocultural [20]. These include, among others, various language barriers [21], mismatched social values [17], discrimination, homesickness, loneliness, immigration policies and others [22]. Communication and interaction issues with local students and lecturers also fall into this category [23; 24] Therefore, it is unsurprising that students studying in their home country in a foreign educational institution may also experience culture shock due to such interactions [25]. As for studying abroad, international students in English-speaking countries experience fewer sociocultural issues than in non- English-speaking countries, where these issues are more serious [13].

Although international students face similar issues worldwide, these issues can be manifested differently depending on subjective and objective factors. The issues that cause culture shock in non-English speaking countries, compared to English speaking countries, have not received the due attention, just as the manifestation of culture shock in the Asian context. That is the purpose of this empirical research. To avoid the need to account for many factors, we focused on the specifics of culture shock experienced by students from one culture who are approximately of the same age and educational level.

In addition, we chose to analyze descriptions made by respondents about their discomforts in the host country, following many scholars practicing qualitative research methods in the educational field and sociocultural adaptation as interviews [26], including semi-structured interviews [10; 27], in-depth interviews [14], narratives [28; 29], content analysis3, and sociocultural interpretations [30; 31]. These descriptions were processed considering quali-quantitative analysis of the obtained data.

The choice of quali-quantitative analysis of statements on problems experienced by students is justified by the complex dynamic relationship between thought and expression. For example, research in social psychology has shown that the frequency of using certain words in speech and writing is related to various psychological aspects of individuals relationships with situations, other people, mental health, etc. [32]. Therefore, a combination of psycholinguistic and linguistic methods of text analysis was used in the empirical research. It was assumed that such an interdisciplinary approach would maximize the consideration of all features of respondents experiences of discomfort (culture shock) related to introduction into a different sociocultural environment.

The following questions guided this research. How international students will describe the experience of culture shock? Does the description of culture shock depend on the length of stay in a different culture and the intensity of their experience?

Materials and Methods

Sample. This research involved 82 Chinese students (53 men and 29 women) who speak Russian, study at South Federal University and stayed in Russia for different periods: up to a year (19 students), a year (14 students), two years (18 students), three years, or more (31 students). The maximum stay in the country is four years. The students had to answer a survey. Also, informed consent was obtained from all respondents for participation in the research/processing of the responses.

Procedure. The survey followed a methodology based on conceptions of cultural differences4. Based on their contact experience with Russian culture, respondents were asked to describe up to three specific cases of discomfort (“culture shock”) that they experienced or witnessed and rate them according to a 5-point system, considering that five points represent the most significant degree of discomfort. The time and length of the description were not limited so that the description could be from one word to several sentences. In addition, respondents indicated their socio-demographic data (gender, age, nationality, time of stay in Russia). The survey used Google Forms, and participation was voluntary and was carried out at a time convenient for respondents.

The resulting descriptions of discomfort were collected and organized into three groups according to the level of severity of culture shock (CS): “low”, “average”, and “high” CS levels. The CS level was determined according to two criteria. The first criterion refers to the overall CS level of each student, based on the sum of the points they attributed to their description of all situations of discomfort (low level of CS – below 7 points; average level of CS – from 7 to 9 points, and high level of CS – above 9 points, considering the limit of 15 points). The second criterion considers the specific level of CS for each described situation. (low level of CS – 1–2 points; average level of CS – 3 points; high level of CS – 4–5 points).

To answer the questions raised in the previous section, this research used a correlation analysis5, where the CS severity level represented the dependent variable and independent variables were distributed according to several factors, namely:

- The length of students stays in Russia: less than a year, one year, two years, three years, and more than three years.

- Linguistic formal elements present in the situations of discomfort described by students:

– the size of descriptions (by the number of words used in statements);

– the use of complex and simple sentences in descriptions;

– the use of lexemes (nouns, adjectives, and verbs);

– the use of individual words, mainly adverbs (quantitative, qualitative, and intensifiers) and pronouns (including the pronoun “I” and derivatives from it, as an expression of personal bias towards the described cases);

– formal marking of the tense category in sentences (the use or non-use of the formal ending of the past tense).

In analyzing the correlation between the time students spent in Russia and the severity of culture shock, each students general CS level was considered. The specific CS level in each situation was used to analyze the correlation between the CS level and language factors. A total of 188 statements were analyzed.

Methods. The analysis results were processed based on the “R” software, with a chi-square test for independence and Cramers V test, which measures the size of the effect of independent variables on the dependent variable. Regarding the analysis of personal bias in the described CS cases, a binomial test and a z-test for the difference in proportions were used, and an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out to describe the use of adverbs.

Results

When analyzing the correlation between the length of stay of Chinese students in Russia and their CS severity level, the results in table 1 were obtained.

T a b l e 1. Relation between length of stay in Russia and culture shock

Length of stay in Russia | Culture shock | |||||

Low | Average | High | ||||

Freq | % | Freq | % | Freq | % | |

Less than a year | 19 | 79 | 5 | 21 | – | – |

One year | 2 | 14 | 7 | 50 | 5 | 36 |

Two years | 10 | 56 | 4 | 22 | 4 | 22 |

Three years | 14 | 88 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 6 |

More than three years | 7 | 78 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 22 |

Notes: χ2 = 26.74; df = 8; p-value < 0.001; Cramers V = 0.406.

Source: Hereinafter in this article all tables were drawn up by the authors.

The data presented in table 1 show no assessment of a high level of culture shock among students who have lived in a new sociocultural environment (in Russia) for less than one year. The level of discomfort increases among those students who have lived in Russia for a year or two years and then decreases among those who have lived in Russia for three years or more than three years. Accordingly, newly arrived students show a low CS level. This situation changes for students who have lived in Russia for one or two years, with a decrease in low CS rates. For those students who have lived in Russia for three years or more, the indicators of low CS increase quite strongly. The results of the chi-square test show that the distribution of the data is significant. In turn, Cramers V test shows a moderate effect of the factor “students length of stay in a foreign country” on the expression of their culture shock. Thus, the length of stay in the country is related to the level of assessment of the culture shock intensity.

Another potential indicator of CS severity could be the type of sentence the students write. Our analysis suggests that simpler sentences may be associated with higher levels of culture shock. This could imply that negative emotions are expressed more succinctly, possibly due to the respondents cultural characteristics. However, as seen in table 2, the statistics do not show significant results, leaving room for further investigation.

T a b l e 2. Expression of simple and complex clauses and association with culture shock

Culture shock | Clause complexity | |||

Simple clauses | Complex clauses | |||

Freq | % | Freq | % | |

Low | 22 | 50 | 22 | 50 |

Average | 25 | 64 | 14 | 36 |

High | 24 | 62 | 15 | 38 |

Notes: χ2 = 1.9532; df = 9; p-value > 0.05; Cramers V = 0.127.

Another factor related to formal elements of the statement on the level of culture shock was the utterances length. On the one hand, the analysis showed that text coherence is less complex when describing situations with a high degree of CS, with more simple clauses being used. On the other hand, analysis of the utterances length regarding the number of words used shows a different scenario. More than half of the statements expressing a low level of culture shock are small, up to 3 words, and half of the statements rated as a high level of culture shock are of medium size (4 and 7 words). Table 3 shows the results regarding the size of utterances.

T a b l e 3. Length of statements considering the number of words and culture shock

Culture shock | Statement length | |||||

Small length (until 3 words) | Average length (from 4 to 7 words) | Big length (more than 7 words) | ||||

Freq | % | Freq | % | Freq | % | |

Low | 56 | 60.2 | 21 | 22.5 | 16 | 17.2 |

Average | 12 | 27.3 | 14 | 31.8 | 18 | 40.9 |

High | 13 | 26.0 | 25 | 50.0 | 12 | 24.0 |

Notes: χ2 = 26.661; df = 4; p-value < 0.001; Cramers V = 0.267.

This result is interesting if compared with the distribution of nouns, adjectives, and verbs in the students statements. This comprehensive approach provides a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between language use and culture shock. Table 4 presents the distribution of these parts of speech in relation to the culture shock level among students.

Table 4 shows that adjectives are more frequent when describing low-level culture shock situations. At comparison with the description of situations with a high culture shock level, the difference in the use of adjectives exceeds 12%. To get an idea of the decrease in the use of adjectives when describing situations of a high degree of CS, consider the adjective “Russian” – the most used in descriptions of situations of all levels of CS. When describing situations with a low CS level, the adjective “Russian” was used 15 times, while in descriptions of situations with a high degree of CS, such an adjective was used only three times. Moreover, most cases (53% of those who used this adjective) occur among students with a low CS level living in a new sociocultural environment for up to 1 year. This may be due to the fact that when coming to a new environment students feel a need for providing comparisons between cultures. The new environment attracts the attention of the students, and they use adjectives to evaluate the situation as positive or negative. As the level of CS increases, the lesser the students will use adjectives, but, when using this part of speech, they will choose to employ adjective of negative connotation such as “холодный” (cold), “недружелюбный” (unfriendly), “неясный” (unclear), etc.

T a b l e 4. Distribution of substantives, adjectives, and verbs and CS level

Culture shock | Grammatical category | |||||

Substantives | Adjectives | Verbs | ||||

Freq | % | Freq | % | Freq | % | |

Low | 113 | 50 | 65 | 29 | 50 | 22 |

Average | 107 | 50 | 48 | 22 | 59 | 28 |

High | 75 | 52 | 22 | 15 | 48 | 33 |

Notes: χ2 = 9.6266; df = 4; p-value < 0.05; Cramers V = 0.085.

When analyzing adverbs (Table 5), we identified those that appeared more than two times in the respondents descriptions.

T a b l e 5. Use of adverbs in the description of CS cases

Adverb | Culture Shock | |||||

Low | Average | High | ||||

Freq | % | Freq | % | Freq | % | |

Пока (so far) | 10 | 27 | – | – | – | – |

Слишком (too much) | 5 | 13 | 2 | 7 | – | – |

Много (many) | 4 | 10 | – | – | 2 | 6 |

Очень (very) | 3 | 8 | 8 | 30 | 6 | 18 |

Иногда (sometimes) | – | – | 4 | 15 | – | – |

Быстро (fast) | 2 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 6 |

Хорошо (well) | – | – | 2 | 7 | – | – |

Мало (little, few) | – | – | 2 | 7 | 2 | 6 |

Долго (long) | – | – | – | – | 2 | 6 |

Несколько (some) | – | – | – | – | 2 | 6 |

Type frequency | 20 | – | 13 | – | 23 | – |

Token frequency | 39 | – | 27 | – | 33 | – |

Notes: F-test = 0.2363; p-value > 0.05.

The F statistics represents the ratio of between-group variance to within-group variance. In this case, the F-statistic value is 0.2363, which is a relatively low value. At the same time, the p-value was 0.7911 (bigger than 0.05). This high p-value indicates no statistically significant differences between the average adverbs frequencies for different culture shock levels. Therefore, insufficient evidence supports the claim that the average frequencies of adverbs differ for at least one culture shock level.

However, let us turn to a qualitative analysis of the use of adverbs. As one can see, the adverb “пока” (“so far” in Russian) is found only when students describe situations causing low CS, and the frequency of its use is almost a third of the total of adverbs. Moreover, 80% of the use of this adverb occurs in the description of culture shock by students staying in Russia for up to a year. Performing the syntactic role of a circumstance, this adverb of time reflects the present (“here and now”), to a certain extent of uncertainty that a situation of discomfort will happen or not in the future. In these cases, it was possible to note descriptions as the following:

1) “Пока мои контакты с русскими идут хорошо”.

2) “Пока я учусь на философском факультете и русские одноклассники и учителя, с которыми я общаюсь, дружелюбны”.

3) “Храните свою одежду, пока вы находитесь на выставке”.

The most common adverb when assessing moderate CS is “очень” (very). Although it is also used by respondents at other CS levels, it is in this category that the frequency of its use is highest, and, as with the use of the adverb “so far” in the first group, it accounts for 30% of the total number of adverbs. The second most common adverb in this group is “sometimes,” which is found only in this group of the CS assessment, also an adverb of time and means impermanence, the presence of something from time to time, as in the following example:

4) “Приветственный этикет, по-китайски будет пожимать руки, но в России иногда люди будут обниматься”.

When assessing discomfort to a high degree (the group of statements of high CS), the adverb “очень” (very) emerges as a critical indicator, underscoring the severity of culture shock. Despite its frequency being only 18% in percentage terms, this adverbs significance is evident, especially when compared to other adverbs.

Thus, even with a low CS, respondents are not confident in the stability of the current situation and are not sure that they will not have problems when adapting to a different culture in the future. As the severity of CS increases, one can observe a more significant variation in adverbs describing situations that cause it. In general, it can be noted that adverbs are one of the critical indicators of the severity of culture shock, considering possible linguistic measures of CS.

When analyzing the expression of personal bias in the cases of CS that occurred, the pronoun “Я” (I) and its derivatives (“me”, “to me”, “for me”, and “with me”) were considered depending on the time of stay in Russia, as one can see in table 6.

T a b l e 6. Personal bias towards described CS cases

Length of stay in another culture | Pronoun “I” and derivatives | |

Freq | % | |

A year or less | 27 | 57.4 |

From one to four years | 20 | 42.6 |

Notes: p-value > 0.05; z-test = 1.4439; p-value > 0.05.

As for the analysis of the category “tense,” the morphological type of Russian tense markers was considered (the only ending denoting tense is the past tense, which typologically characterizes Russian as a past X non-past language). So, the dichotomy of the past (endings of the past tense in the verbs occurring in the statements) and non-past (the absence of such an ending, that is, the expression of the present and future tenses). Not all utterances consisted of complete sentences, so utterances that included only a negative response (e.g., “no” or “not yet”) or utterances that only identified one word or group of words as the cause of discomfort were excluded (e.g., “cockroaches”, “food”, “language barrier”).

Based on the results obtained, it can be noted that statements in the past tense describe concrete and specific situations (examples 5 and 6) in contrast to statements in the non-past tense (in most cases, in the present tense), when general situations are described, or the general opinion of the participant is expressed (examples 7 and 8).

5) “Незнакомый попросил у меня денег”.

6) “На улице встретила пьяницу”.

7) “Русские любят сладости”.

8) “На улице меня кто-то просит рубль. Это абсолютно невозможно в Китае”.

Table 7 presents the results of this analysis.

T a b l e 7. Relation of grammatical category of tense and the culture shock level

Culture shock | Grammatical tense category | |||

Non-past | Past | |||

Freq | % | Freq | % | |

Low | 39 | 97.5 | 1 | 2.5 |

Average | 27 | 81.8 | 6 | 18.2 |

High | 29 | 78.4 | 8 | 21.6 |

Notes: χ2 = 6.7945; df = 2; p-value < 0.05; Cramers V = 0.249.

The statistical analysis underscores the significance of the tense category, with a moderate effect (as per the Cramers V test). This finding suggests that participants prefer using the past tense when encountering moderate to high culture shock levels. This may be related to some specific situation from which students are unable to free themselves and which constitutes a point of assessment of culture shock as high.

Having performed the present analysis, it is clear that some factors demonstrated statistical significance, while others did not. This does not mean that the factors with no statistical significance themselves are not relevant, but that the framework adopted during the research may require some improvement. On the other hand, the results obtained here already allow for a significant set of discussions and conclusions.

Discussion and Conclusion

The first thing to draw attention to is the connection between the culture shock level and the time Chinese students spent in Russia. According to the results, students living in a new sociocultural environment for less than one year experience a low CS level. For those living in Russia for one or two years, CS increases. Then, for students living in a new sociocultural environment for three years or more, a low CS is observed and less pronounced than for newly arrived students. As it is possible to observe, this is entirely consistent with K. Oberg and his followers ideas about the stages of culture shock. To a certain extent, these stages described by K. Oberg apply to the respondents who participated in this research. One evidence lies in the frequency of use of the adjective “Russian” as a comparison of their own and another culture by students living in Russia for about a year.

This is another confirmation that CS is an integral part of sociocultural adaptation, and as one enters another culture, CS also changes. The findings are consistent with Obergs understanding of the stages of culture shock. Although some studies [33] adjust the u-shaped and 3-stage model of social adaptation and the model of S. Lysgaard they agree with this model6. Moreover, one can assume that what contributes to successful adaptation is a low level of culture shock. Since we identified other periods, we did not set out to check the obtained data for full compliance with this model. Thus, we cannot say this with complete confidence because, according to S. Lysgaard, adaptation is easy and successful when living for up to 6 months, difficult and unpleasant when staying from 6 to 18 months, and good for staying longer than 18 months. However, the dynamics of CS obtained in this study and the S. Lysgaard model of social adaptation coincide.

From M.J. Bennetts point of view7, the low level of CS can be explained by the fact that the first stage of adaptation involves the denial of intercultural differences, and the second stage, protection from cultural differences, naturally increases culture shock. The next three steps (minimizing cultural differences, recognizing cultural differences, adapting to cultural differences, and integrating cultural differences) help reduce CS.

Regarding the level of culture shock among Chinese students in our study, respondents experiencing medium or high CS, according to the data obtained, prefer to describe the inconvenience caused in the past tense, i.e., this is already a past stage for them. In this regard, the results of a study by R.J. North and colleagues are interesting, showing that participants who integrated acceptance and positive reappraisal of the situation wrote less about the past and more about the future and used many words in the writing process. In addition, they used fewer first-person singular pronouns (e.g., “I”) and more often used first-person plural pronouns (e. g., “We”) [34].

In our case, the students who experienced severe CS overcame and accepted the current situation. This may be confirmed, although indirectly, by the fact that statements in the past tense describe concrete and specific life situations, in contrast to statements in the non-past tense (in most cases, in the present tense), which describe general standard situations or the participants general opinion. The higher the culture shock level, the simpler the sentences, i.e., negative emotions tend to be expressed briefly. However, the latter may be associated not with the CS severity level but with the respondents sociocultural characteristics. However, analyzing the respondents use of adverbs, it can be noted that they are not sure that situations causing perplexity or intense discomfort could occur in the future.

The personal bias towards the situations that caused CS, and its independence from the time spent in a different culture, may be due to the cases themselves. Numerous studies have shown that using “I” pronouns is associated with many psychological phenomena, including situational acceptance, as discussed above, and relationship satisfaction [32]. At the same time, the first-person singular pronoun indicates an independent “I” and is associated with the level of individualism in society and the general requirement for the explicit use of personal pronouns in the language [35]. The change in the use of personal pronouns, conceptually related to individualism-collectivism, has characterized modern Chinese society in recent decades, with the increasing use of individualistic pronouns and a decreasing use of collectivistic pronouns [36]. In addition to sociocultural characteristics, using personal pronouns may be associated with students communication experience and individual characteristics, but this requires additional research.

Restrictions. Undoubtedly, Chinese and Russian cultures have a number of differences, but this study did not consider the influence of cultural distance on the results obtained. The authors recognize the crucial need for longitudinal studies to comprehensively understand the culture shock complexities, including the process of overcoming these challenges. This may become a prospect of further research in this area.

This research expands and substantiates the conceptions of culture shock as an integral part of sociocultural adaptation. The data analyzed confirm not only its dependence on the length of stay of international students in another country but also a complex assessment of culture shock. On the one part, culture shock causes unpleasant (sometimes extreme) experiences. However, having “suffered”, a person accepts the current situation, contributing to her further sociocultural adaptation. A low level of shock, although not causing such strong emotions, gives no confidence in a successful adaptation. The obtained results can help in providing tutoring support to Chinese students and in developing programs that facilitate their socio-cultural adaptation. Although the study involved only Chinese students, the results can be considered when studying the sociocultural adaptation of students of different nationalities.

1 Oberg K. Cultural Shock: Adjustment to New Cultural Environments. Practical Anthropology. 1966;(7):177–182. Available at: https://www.sci-hub.ru/10.1177/009182966000700405 (accessed 28.03.2025).

2 Oberg K. Cultural Shock: Adjustment to New Cultural Environments.

3 Ryumshina L., Belousova A., Berdyanskaya Y., Altan-Avdar I. Symmetrical and Asymmetrical Approaches to Communication in Education in Distance Learning. In: Beskopylny A., Shamtsyan M. (eds) XIV International Scientific Conference “INTERAGROMASH 2021”. Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems. Cham.: Springer; 2022;247:471–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80946-1_45

4 Bardier G.L. [Social Psychology of Tolerance]. In: [Abstract of the Dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Psychological Sciences]. Norma: Saint Petersburg; 2007. 46 p. (In Russ.) Available at: http://irbis.gnpbu.ru/Aref_2007/Bardier_G_L_%202007.pdf (accessed 28.03.2025).

5 Levshina N. How to Do Linguistics with R: Data Exploration and Statistical Analysis. Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company; 2015. https://doi.org/10.1075/z.195

6 Lysgaard S. Adjustment in Foreign Society: Norwegian Fulbright Grantees Visiting the United States. International Social Science Bulletin. 1955;7:45–51.

7 Bennett M.J. A Developmental Approach to Training for Intercultural Sensitivity. International Journal of Intercultural Relations. 1986;10(2):179–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(86)90005-2

Об авторах

Любовь Ивановна Рюмшина

Южный федеральный университет

Автор, ответственный за переписку.

Email: ryumshina@sfedu.ru

ORCID iD: 0000-0003-2228-8140

SPIN-код: 7027-4206

Scopus Author ID: 6506836314

ResearcherId: P-6488-2015

доктор психологических наук, профессор кафедры социальной психологии

Россия, 344006, г. Ростов-на-Дону, ул. Большая Садовая, д. 105, корп. 42Диего Лейте де Оливейра

Федеральный университет Рио-де-Жанейро

Email: diegooliveira@letras.ufrj.br

ORCID iD: 0000-0003-0601-4131

Scopus Author ID: 55138232900

ResearcherId: ACF-5855-2022

доктор лингвистики, доцент факультета искусств

Бразилия, 21941-917, г. Рио-де-Жанейро, ул. Орасио Маседа, д. 2151Список литературы

- Sussman N.M. The Dynamic Nature of Cultural Identity Throughout Cultural Transitions: Why Home is Not so Sweet. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2000;4(4):355–373. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0404_5

- Tkachenko E.A. “Cultural Shock” in the Process of Adaptation of Foreign Medical Students in the Professional Environment of Russian Universities. Society: Philosophy, History, Culture. 2024;(10):138–144. (In Russ., abstract in Eng.) https://doi.org/10.24158/fik.2024.10.19

- Alkubaidi M., Alzhrani N. “We Are Back”: Reverse Culture Shock Among Saudi Scholars After Doctoral Study Abroad. SAGE Open. 2020;10(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020970555

- Geeraert N., Demoulin S. Acculturative Stress or Resilience? A Longitudinal Multilevel Analysis of Sojourners’ Stress and Self-Esteem. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2013;44(8):1241–1262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022113478656

- Guang X., Charoensukmongkol P. The Effects of Cultural Intelligence on Leadership Performance among Chinese Expatriates Working in Thailand. Asian Business & Management. 2022;21(1):106–128. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41291-020-00112-4

- Moufakkir O. Culture Shock, What Culture Shock? Conceptualizing Culture Unrest in Intercultural Tourism and Assessing Its Effect on Tourists’ Perceptions and Travel Propensity. Tourist Studies. 2013;13(3):322–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797613498166

- Setti I., Sommovigo V., Argentero P. Enhancing Expatriates Assignments Success: The Relationships between Cultural Intelligence, Cross-Cultural Adaptation and Performance. Current Psychology. 2020;41:4291–4311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00931-w

- Romanovskaia O.E., Ilina D.M. Social and Cultural Adaptation of Foreign Students in a Russian University in the Context of Academic Mobility. Volga Region Pedagogical Search. 2019;(2):62–68. (In Russ., abstract in Eng.) https://doi.org/10.33065/2307-1052-2019-2-28-62-68

- Huang H., Liu H., Huang X., Ding Y. Simulated Home: An Effective Cross-Cultural Adjustment Model for Chinese Expatriates. Employee Relations: The International Journal. 2020;42(4):1017–1042. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-09-2019-0378

- Mumtaz S., Nadeem S. Understanding the Integration of Psychological and Socio-Cultural Factors in Adjustment of Expatriates: An AUM Process Model. Sage Open. 2022;12(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221079638

- Bierwiaczonek K., Waldzus S. Socio-Cultural Factors as Antecedents of Cross-Cultural Adaptation in Expatriates, International Students, and Migrants: A Review. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2016;47(6):767–817. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022116644526

- Tang L., Zhang C. Global Research on International Students Intercultural Adaptation in a Foreign Context: A Visualized Bibliometric Analysis of the Scientific Landscape. SAGE Open. 2023;13(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231218849

- Oduwaye O., Kiraz A., Sorakin Y. A Trend Analysis of the Challenges of International Students Over 21 Years. SAGE Open. 2023;13(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231210387

- do Amaral C.C.B., Romani-Dias M., Walchhutter S. International Brazilian Students: Motivators, Barriers, and Facilitators in Higher Education. SAGE Open. 2022;12(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221088022

- Yilmaz K., Temizkan V. The Effects of Educational Service Quality and Socio-Cultural Adaptation Difficulties on International Students Higher Education Satisfaction. SAGE Open. 2022;12(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440221078316

- Marinenko O.P. International Students Need for University Support. Integration of Education. 2024;28(3):334–346. (In Russ., abstract in Eng.) https://doi.org/10.15507/1991-9468.116.028.202403.334-346

- Ryumshina L.I. Socio-Cultural Adaptation of Students to Education Abroad: The Approach of Russian and Foreign Psychologists. Psychology. Historical-Critical Reviews and Current Researches. 2023;12(8A):111–118. (In Russ., abstract in Eng.) https://elibrary.ru/jvbdqd

- Novikova S.V., Zaydullin S.S., Valitova N.L., Kremleva E.S. Difficulties in the Implementation of International Academic Mobility Programs: Students Stance. Russian-German Experience in Solving Problems in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Integration of Education. 2023;27(1):10–32. (In Russ., abstract in Eng.) https://doi.org/10.15507/1991-9468.110.027.202301.010-032

- Volkov Yu.A., Bashеrov O.I., Yashina Yu.V., Savelieva M.N. Problems of Adaptation of International Students in a New Academic Environment: Cultural, Academic and Psychological Aspects. Education Management Review. 2024;14(10–1):180–190. Available at: https://emreview.ru/index.php/emr/article/view/1769?articlesBySameAuthorPage=4 (accessed 28.03.2025).

- Dovchin S. The Psychological Damages of Linguistic Racism and International Students in Australia. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. 2020;23(7):804–818. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2020.1759504

- Brazhnik L.M., Galiev L.M., Galiullin R.R., Tarasov A.M., Shakirova L.R. Ethnooriented Methods of Teaching Russian as a Foreign Language to Arabic-Speaking Students. Journal of Pedagogical Innovations. 2023;(2):113–123. (In Russ., abstract in Eng.) https://doi.org/10.15293/1812-9463.2302.11

- Kuznetsova O.V., Deriugin P.P., Kremnyov E.V. Social Adaptation of Chinese Students in Russia as a Managerial Problem. Research Result. Sociology and Management. 2024;10(3):150–167. https://doi.org/10.18413/2408-9338-2024-10-3-1-0

- Shah A.A., Lopes A., Kareem L. Challenges Faced by International Students at Kwantlen Polytechnic University. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Perspectives in Higher Education. 2019;4(1):111–135. https://doi.org/10.32674/jimphe.v4i1.1408

- Gebru M.S., Yuksel-Kaptanoglu I. Adaptation Challenges for International Students in Turkey. Open Journal of Social Sciences. 2020;8(9):262–278. https://doi.org/10.4236/jss.2020.89021

- Pyvis D., Chapman A. Culture Shock and the International Student ‘Offshore’. Journal of Research in International Education. 2005;4(1):23–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240905050289

- Triyanto. The Academic Motivation of Papuan Students in Sebelas Maret University, Indonesia. Sage Open. 2019;9(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018823449

- Raspaeva G.D., Markus A.M., Yaroslavova E.N. Socio-Cultural Adaptation of International Students at a Russian University: A Communicative Aspect. Bulletin of the South Ural State University. Ser.: Education. Educational Sciences. 2022;14(1):76–87. (In Russ., abstract in Eng.) https://doi.org/10.14529/ped220108

- Dunlop W.L., Westberg D.W. On Stories, Conceptual Space, and Physical Place: Considering the Function and Features of Stories Throughout the Narrative Ecology. Personality Science. 2022;3(1). https://doi.org/10.5964/ps.7337

- Proshkova Z.V., Yeremenko Y.Y. Parental View of Online Schools: Internet Forum Analysis. World of Science. Series: Sociology, Philology, Cultural Studies. 2024;15(3). (In Russ., abstract in Eng.) https://doi.org/10.15862/16SCSK324

- Terkourafi M. Coming to Grips with Variation in Sociocultural Interpretations: Methodological Considerations. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2019;50(10):1198–1215. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022119871634

- Tareva E.G., Dorokhova A.M. Present-Day Intercultural Discourse: Focus on Teaching Languages. MCU Journal of Philology. Theory of Linguistics. Linguistic Education. 2024;(1):124–135. (In Russ., abstract in Eng.) https://doi.org/10.25688/2076-913X.2024.53.1.09

- Simmons R.A., Gordon P.C., Chambless D.L. Pronouns in Marital Interaction: What Do “You” and “I” Say About Marital Health? Psychological Science. 2005;16(12):932–936. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01639.x

- Markovizky G., Samid Y. The Process of Immigrant Adjustment: The Role of Time in Determining Psychological Adjustment. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2008;39(6):782–798. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022108323790

- North R.J., Meyerson R.L., Brown D.N., Holahan C.J. The Language of Psychological Change: Decoding an Expressive Writing Paradigm. Journal of Language and Social Psychology. 2013;32(2):142–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X12456381

- Uz I. Individualism and First Person Pronoun Use in Written Texts Across Languages. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2014;45(10):1671–1678. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022114550481

- Hamamura T., Xu Y. Changes in Chinese Culture as Examined through Changes in Personal Pronoun Usage. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 2015;46(7):930–941. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022115592968

Дополнительные файлы